This could be the most important chapter in this book. If you don’t understand how to open and save files by using the Open dialog and Save sheets or how to use the file and folder system, you’ll have a heck of a time getting the hang of your Mac. Ask any longtime Mac user; the old lament is pretty common: “Well, I saved the file, but now I don’t know where it went.” It happens all the time with new users; if they don’t master these essential techniques, they often become confused about where files are located on their hard drives. Sure, the Sidebar has an item called All My Files that displays all of your files, and Spotlight can find files in milliseconds, but if you have thousands or tens of thousands of files, both can be more of a curse than a blessing.

This chapter is a tonic for finding the file or folder you want. Knowing where your files are is something every Mac user should grok (fully understand). Hang with me and pay attention; everything will soon become crystal clear.

All My Files (in the Sidebar) is a fast and easy way to find a file or folder (although the sheer number of files it displays may overwhelm you, no matter how you sort or arrange them). And Chapter 7 is chock-full of tools and tips for finding files and folders when you misplace them. Furthermore, although you can often find files or folders by using Spotlight, you have to remember enough details about the file or its contents for Spotlight to find it.

At the end of the day, all the aforementioned techniques are useful and good to know, but take it from me: It’s often faster and easier if you know exactly where a file or folder is than to hunt for it.

Later in the chapter, I look at using Open dialogs and Save sheets within applications to find files and folders. You see them only after you launch a program and use that program’s File menu to open or save a file. (For more on launching applications, read the parts of Chapter 5 about icons; for more on creating and opening documents, see the documentation or Help file for the program that you’re using.)

Spotlight (which you discover in Chapter 7) is OS X’s built-in search mechanism. It’s available just about everywhere you look in Mavericks: The magnifying glass on the menu bar, the Toolbar of Finder windows, and Open dialogs and Save sheets. The point is, if you can’t find a file or folder manually as described in the rest of this chapter, try Spotlight.

If you’re the sole person who accesses your Mac, you probably have only one user. Regardless, the folder structure that OS X uses is the same whether you have one user or dozens.

If you’re the sole person who accesses your Mac, you probably have only one user. Regardless, the folder structure that OS X uses is the same whether you have one user or dozens.

Within the Users folder, you find your personal Home folder (which bears your short user name), along with a Shared folder, where you can put files you want to share with other users. All these files are stored in a nested folder structure that’s a bit tricky to understand at first. This structure makes more sense after you spend a little time with it and figure out some basic concepts.

If you display the path bar at the bottom of your windows by choosing View➪Show Path Bar, it’ll start to make sense much sooner.

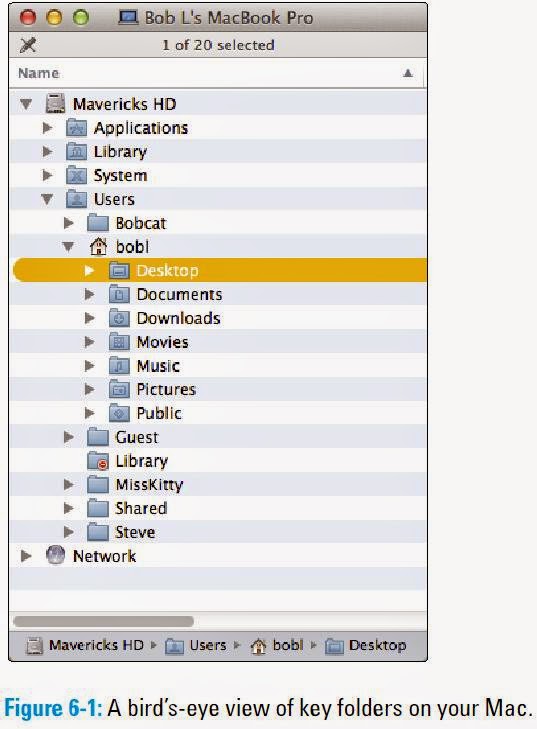

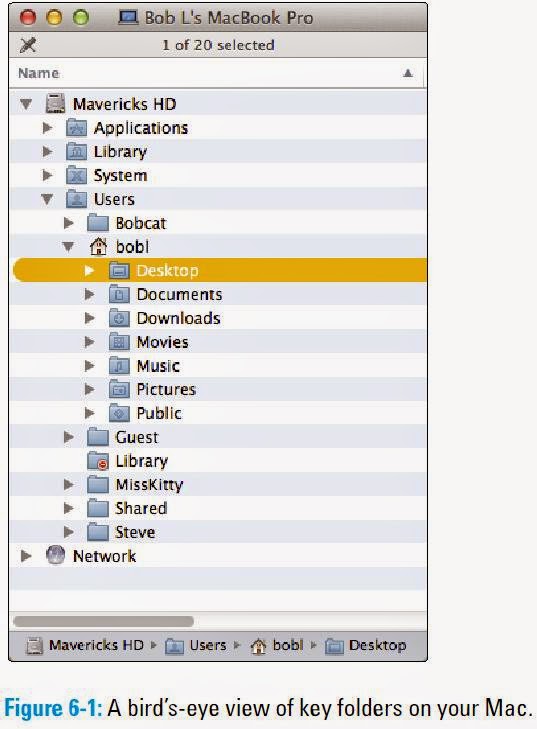

Take a look at Figure 6-1; you can see how these main folders are related to one another. In the sections that follow, you look at each of these folders in more depth and find out more about what’s nested inside each one.

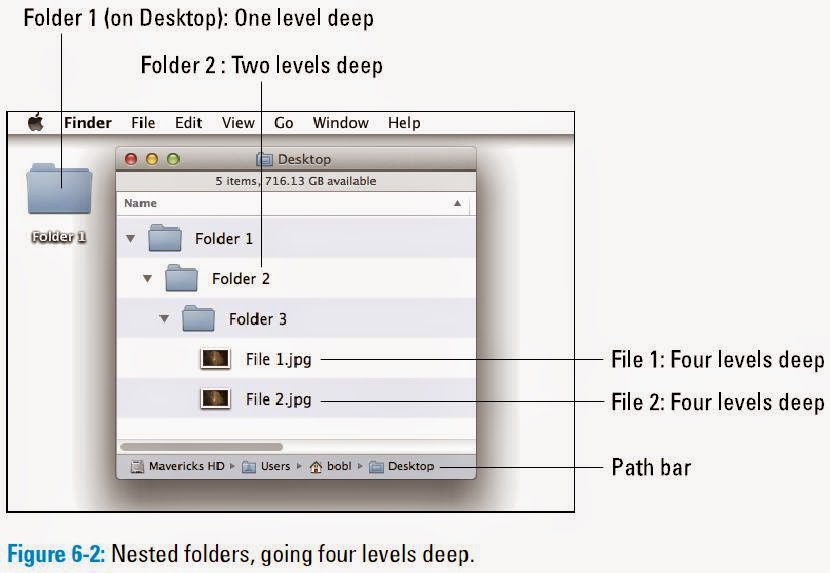

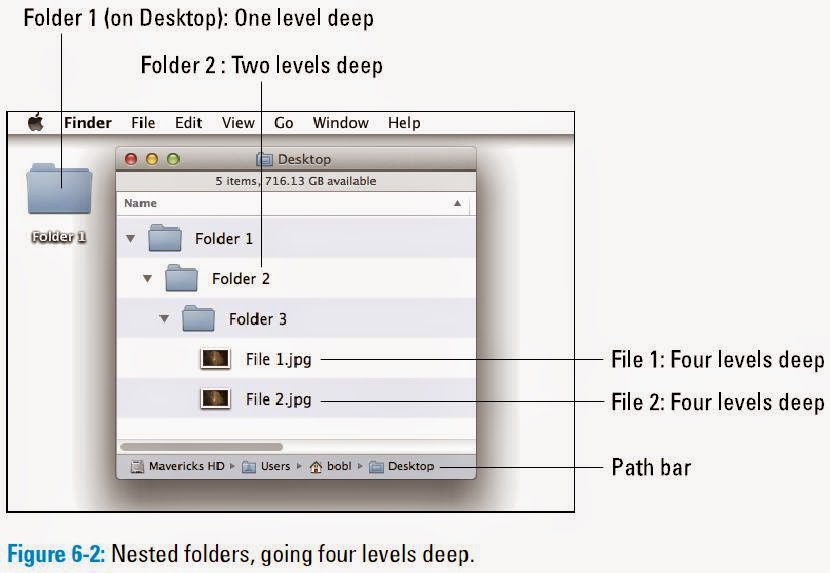

Folders within other folders are often called nested folders. To get a feel for the way nested folders work in OS X, check out Figure 6-2.

Folders within other folders are often called nested folders. To get a feel for the way nested folders work in OS X, check out Figure 6-2.

You can see the following in Figure 6-2:

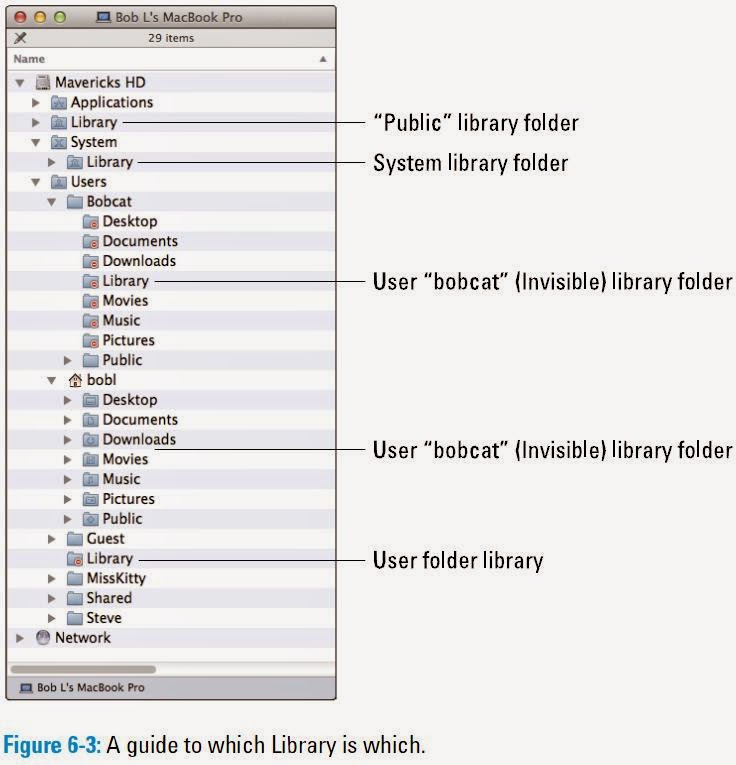

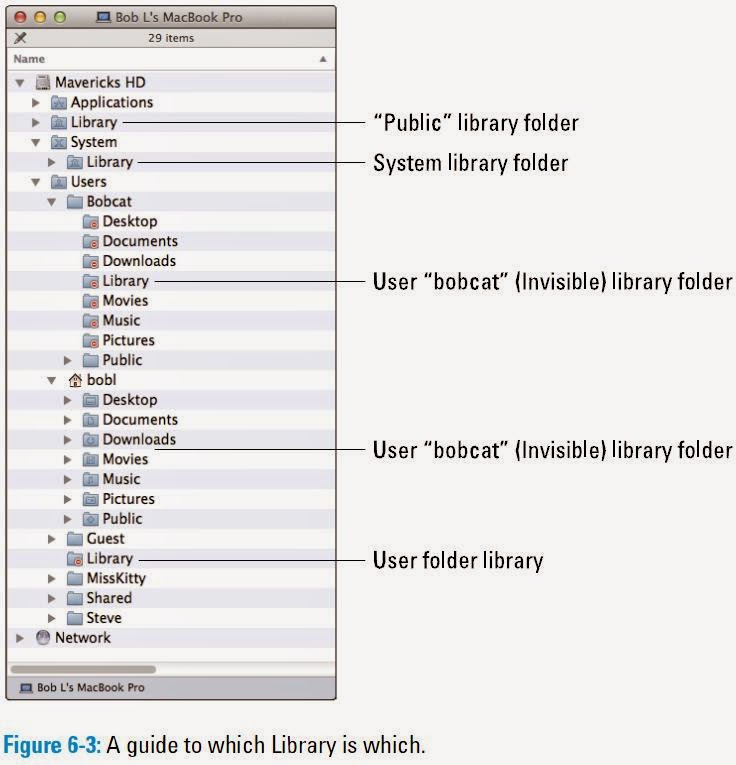

There are actually four or more Library folders on your hard drive: one at the root level of your OS X disk, a second inside the root-level System folder, a third inside the Users folder, and the fourth in your Home folder.

What’s that you say? You don’t see a Library folder inside your Home folder? Well it’s like this: In versions of OS X earlier than OS X Lion (10.7), you would have seen a folder named Library between the Downloads and Movies folders in your Home folder (or mine — bobl — in Figure 6-1). But that was then, and this is now. In OS X Mavericks, the Home Library folder is hidden from view to protect you from yourself. You discover the secret to making it visible if you need it in the “Your personal Library card” section of this chapter, which is coming up.

Leave the /System/Library folder alone. Don’t move, remove, or rename it, or do anything within it. It’s the nerve center of your Mac. In other words, you should never have to touch this third Library folder. You find a bunch of folders inside the Library folder at root level (the “public” Library folder). Most of them contain files that you never need to open, move, or delete.

By and large, the public Library subfolder that gets the most use is the Fonts folder, which houses many of the fonts installed on the Mac. For the most part, fonts can be made available in one of two ways:

Finally, the Library in the Users folder is where OS X stores configuration and preferences files shared by all users.

Don’t remove, rename, or move any files or folders in any of your Library folders unless you’re sure of what you’re doing and why. OS X is very picky about folders in its Libraries being in the proper place and bearing the proper name. While I’m on the subject, you probably shouldn’t remove,

Don’t remove, rename, or move any files or folders in any of your Library folders unless you’re sure of what you’re doing and why. OS X is very picky about folders in its Libraries being in the proper place and bearing the proper name. While I’m on the subject, you probably shouldn’t remove,

rename, or move applications installed by Mavericks in the Applications folder.

Note: Under most circumstances, you won’t actually add items to or remove items from folders in this Library yourself. Software installers usually do the heavy lifting for you by placing all their little pieces in the appropriate Library folders. You shouldn’t need to touch this Library often, if ever. That said, knowing what these folders are — and who can access their contents — might come in handy down the road a piece.

The locations of all these libraries are illustrated in Figure 6-3.

If your Mac is set up for multiple users, only users with administrator (admin) privileges can put stuff in the public (root-level) Library folder. (For more information on admin privileges, check out Chapter 16.)

Leave the System folder alone. Don’t move, remove, or rename it or anything within it. It’s part of the nerve center of your Mac.

The bottom line is that you should, for the most part, restrict yourself to using the folders within your Home folder. If you’re the only user of your Mac, you can pretty much forget about the root level Library. But those with more than one user account on their Mac may someday need to add or remove a file from this folder.

So now you can forget everything outside your Home folder because with few exceptions, that’s where all of your “stuff” will reside.

The Shared folder that you see inside the Users folder allows everyone who uses the Mac to use any files stored there. If you want other people who use your Mac to have access to a file or folder, the Shared folder is the proper place to stash it. You can see the Shared folder under the MissKitty folder in Figure 6-1 earlier in this chapter.

I realize that a lot of people don’t share their Macs with others, and if you’re one of these folks, you may wonder why I keep mentioning sharing and multiple users and the like. Well, OS X is based on the Unix operating system — a multiuser operating system used on high-end servers and workstations that are often shared by several people. OS X has both the benefit of this arrangement and a bit of the confusion caused when a single user (could it be you?) fires up a computer that could be set up for several people. That’s why OS X folders are organized the way they are — with different hierarchies for each user and for the computer as a whole.

I should also mention that each user account has its own preferences and settings and that one user can’t see another user’s files by default.

If your Mac has more than one constant user, consider creating a user account for each person. If you’re a parent, separate user accounts mean you can enable Mavericks’ terrific Parental Controls, which are a very good thing if you ask me. But I’m getting ahead of myself again; Chapter 16 has the scoop on sharing your Mac and Parental Controls.

Your Home folder is the most important folder for you as a user — or at least the one where you stash most of your files. I strongly recommend that you store all the files you create in subfolders within your Home folder — preferably, in subfolders in your Home/Documents folder. The advantage of doing so is that your Home/Documents folder is easy to find, and many programs use it as the default folder for opening or saving a file.

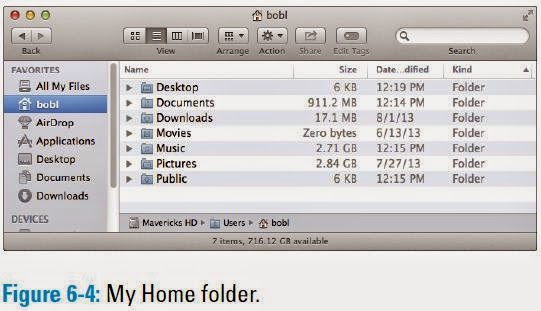

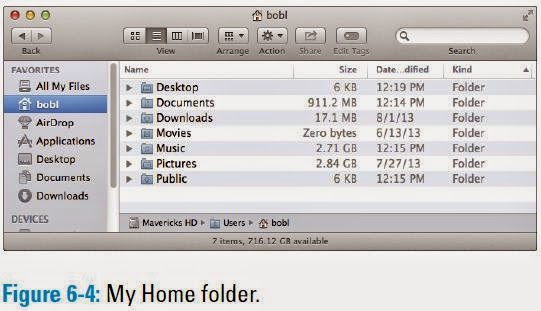

When you open your Home folder, you see a Finder window with a little house icon and your short username in the title bar. Seeing your short username in the title bar tells you that you’re in your Home folder. Every user has a Home folder named after his or her short username (as specified in the Users & Groups System Preferences pane). Figure 6-4 shows that my Home folder is named bobl — the short name I used when I first set up my Mac.

When you open your Home folder, you see a Finder window with a little house icon and your short username in the title bar. Seeing your short username in the title bar tells you that you’re in your Home folder. Every user has a Home folder named after his or her short username (as specified in the Users & Groups System Preferences pane). Figure 6-4 shows that my Home folder is named bobl — the short name I used when I first set up my Mac.

If your Mac has more than one user, you can see the other users’ Home folders in your Users folder, but OS X prevents you from opening files from or saving files to them.

By default, your Home folder has several folders inside it created by OS X. The following four are the most important:

The following are a few more tidbits to keep in mind as you dig around your Home folder:

In the “Finding fonts (and more) in the public Library folder” section, earlier in this chapter, I discuss the Library folder that’s used to specify preferences for the Mac as a whole. But this Library folder is all about you and your stuff.

Be cautious with all Library folders. OS X is very persnickety about how the folders and files within it are organized. As I discuss earlier in the chapter, you can add items to and remove items safely from most public or Home Library folders, but leave the folders themselves alone. If you remove or rename the wrong folder, you could render OS X inoperable. It’s like the old joke about the guy who said to the doctor, “It hurts when I do that,” and the doctor replies, “Then don’t do that.”

To find your hidden Home/Library folder, do this:

If you don’t want to have to do this dance every time you want to open your Home/Library, Mavericks has a new option for you: There’s now a Show Library Folder check box in the View Options window (choose View➪Show/Hide View Options or press ⌘+J). Select it, and your Home/Library will be visible evermore (or at least until you deselect the check box).

Some of the most important standard folders in the Library folder include the following:

When you save a file, you’re committing a copy to a disk — whether it’s a disk connected directly to your Mac, one available over a network, or a removable disk such as a USB flash drive or portable hard disk.

Lion introduced three new features — Resume, Auto Save, and Versions — to make your life easier. In previous versions of OS X, applications generally showed a blank page or nothing at all when you launched them. Mavericks’ Resume feature automatically reopens all windows that were onscreen when you quit the app. So, when you launch the app again, all the windows are reopened in the same position onscreen as when you quit. Best of all, Resume seems to work with most third-party apps.

Programs have offered Auto Save before, but now it’s baked into OS X. Auto Save automatically saves versions of your work as you work, when you pause, and every five minutes, whether you need it or not.

For as long as we’ve had Macs, we’ve saved unique versions of our files, creating and managing them with the Save As command or by duplicating and renaming them in the Finder. Now Mavericks (like Lion and Mountain Lion before it) takes over version control for you by automatically saving versions as described in the preceding paragraph.

That’s the good news, but there’s also bad news . . . although Auto Save and versions are baked right into OS X, third-party apps require a software update before they can take advantage of these features. So please don’t get too comfortable with Auto Save and Versions until you’re sure that your applications take advantage of these features. Most third-party apps still rely on the good old Save and Save As commands, which have been around since time immemorial (or at least since 1984).

In the following sections, I show you how to save your masterpieces. Prevent unnecessary pain in your life by developing good saving habits. I recommend that you save your work (or save a version in apps that support versions)

If you don’t heed this advice — and the program that you’re using crashes while switching programs, printing, or sitting idle (the three likeliest times for a crash) — you may lose everything you did since your last save or saved version. The fact that a program crash doesn’t bring down the entire system or force a restart is small consolation when you’ve lost everything you’ve typed, drawn, copied, pasted, or whatever since the last time you saved or saved a version.

In a few sections of this book, I ask you not only to read the instructions while sitting in front of your Mac but also to perform each step of the instructions as described. This section is one of them. If you read it and follow along, I can pretty much guarantee that it’ll make sense. If you read it somewhere other than at your Mac, it could be a mite confusing.

Saving a file works pretty much the same way in any application you use to create documents. For this example, I use OS X’s word processing application, TextEdit, but the process will be very similar in Microsoft Word, Adobe Photoshop, Apple Keynote, or any other application.

If you’re going to follow along as I recommend, please launch the TextEdit program now (it’s in your Applications folder), click the New Document button or choose File➪New, and type a few words on the Untitled page that appears after you launch it.

Now that we’re both on the same page, both literally and figuratively, here’s how saving a file works: When you choose to save a file for the first time (by choosing File➪Save or pressing ⌘+S), a Save sheet appears in front of the document that you’re saving, as shown in Figure 6-6. I call this a basic Save sheet (as opposed to an expanded Save sheet, which I get to in a moment):

When you use apps that don’t support Auto Save and Versions, I beg you to get into the habit of pressing ⌘+S often. It can’t hurt — and just might save your bacon someday.

One last thing: In Figures 6-6, 6-7, and 6-8, I used the Save sheet for TextEdit as an example. In programs other than TextEdit, the Save sheet might contain additional options, fewer options, or different options, and therefore may look slightly different. The File Format menu, for example, is a feature specific to TextEdit; it might not appear in other applications’ Save sheets. Don’t worry. The Save sheet always works the same way, no matter what options it offers.

Before I get into the details, you may be wondering why you would want to save an existing file with a different name. So here’s a good (albeit kind of rude) example: Suppose that you have two cousins, Kate and Nancy. You write Kate a long, chatty letter and save this document with the name Letter to Kate. Later, you decide that you want to send almost the same letter to Nancy, but you want to change a few things. So you change the part about your date last night and replace all references to Kate’s husband, Kevin, with references to Nancy’s husband, Norman. (Aren’t computers grand?)

So you make all these changes in Letter to Kate, but you haven’t resaved this document yet, and although the document on your screen is actually a letter to Nancy, its filename is still Letter to Kate. Think of what would happen if you were to save it now without using the Save As feature: Letter to Kate reflects the changes that you just made. (The stuff in the letter meant for Kate is blown away, replaced by the stuff that you just wrote to Nancy.) Thus the filename Letter to Kate is inaccurate. Even worse, you might no longer have a copy of the original letter you sent to Kate! The solution? Just use Save As or Duplicate to rename this file Letter to Nancy by choosing File➪Save As or File➪Duplicate.

If you chose Save As: A Save sheet appears, in which you can type a different filename in the Save As field. You can also navigate to another folder, if you like, and save the newly named version of the file there. Now you have two distinct files: Letter to Kate and Letter to Nancy. Both contain the stuff they should, but both started life from the same file.

If you chose Duplicate: The title bar of the document becomes editable so you can change its name without even seeing a Save sheet. (Refer to the figure in the earlier sidebar, “Does it have Auto Save and Versions or not?”) Press Enter or Return, and the renamed file will be saved in the same folder as the original. Or, if you want to save the newly renamed file in a different location, choose File➪Move To or click the little triangle to the right of the document’s name, choose Move To in its pop-up menu, and then from the pop-up menu, select a folder in which to save the file.

Now that you understand what Save As or Duplicate are all about, here’s an easier way to get the same result: Before you start, duplicate the document in the Finder (choose File➪Duplicate or press ⌘+D). Rename the copy and open it. This way, when you’re done making changes, you don’t have to remember to choose Save As; you can just perform your habitual Save. This approach also protects you from accidentally saving part of the letter to Nancy without changing the file’s name first (which you’re likely to do if you’re following my advice about saving often). So when you decide that you’re going to reuse a document, choose Save As (or duplicate and rename the file) before you begin working on it, just to be safe.

Versions gives you the benefits of Save As without any action on your part, many programs still lack support for Auto Save and Versions at press time. And, in fact, some of Apple’s apps, as well as most third-party apps, still use the Save As technique, and I expect that to be the status quo for quite some time. But since some of Apple’s offerings (most notably TextEdit) use Auto Save and Versions, I’d be remiss if I glossed over the new way of doing things.

One last thing: If the app you’re using supports Mavericks’ Versions, it creates a snapshot called a Version automatically as you work, when you pause, every five minutes, and every time you choose File➪Save (⌘+S). Choose File➪Revert To➪Browse All Versions to compare different versions of the document you’ve saved side-by-side, as shown in Figure 6-9.

Figure 6-9 is actually Mavericks’ Time Machine backup utility displaying the various Versions. Read more about Time Machine in Chapter 18.

This chapter is a tonic for finding the file or folder you want. Knowing where your files are is something every Mac user should grok (fully understand). Hang with me and pay attention; everything will soon become crystal clear.

All My Files (in the Sidebar) is a fast and easy way to find a file or folder (although the sheer number of files it displays may overwhelm you, no matter how you sort or arrange them). And Chapter 7 is chock-full of tools and tips for finding files and folders when you misplace them. Furthermore, although you can often find files or folders by using Spotlight, you have to remember enough details about the file or its contents for Spotlight to find it.

At the end of the day, all the aforementioned techniques are useful and good to know, but take it from me: It’s often faster and easier if you know exactly where a file or folder is than to hunt for it.

Later in the chapter, I look at using Open dialogs and Save sheets within applications to find files and folders. You see them only after you launch a program and use that program’s File menu to open or save a file. (For more on launching applications, read the parts of Chapter 5 about icons; for more on creating and opening documents, see the documentation or Help file for the program that you’re using.)

Spotlight (which you discover in Chapter 7) is OS X’s built-in search mechanism. It’s available just about everywhere you look in Mavericks: The magnifying glass on the menu bar, the Toolbar of Finder windows, and Open dialogs and Save sheets. The point is, if you can’t find a file or folder manually as described in the rest of this chapter, try Spotlight.

6.1 Understanding the OS X Folder Structure

Start by looking at the folder structure of a typical OS X installation. Open a Finder window and click the icon for your hard drive (which is typically called Macintosh HD) in the Sidebar. You should now see at least four folders: Applications, Library, System, and Users. Within the Users folder, each user with an account on this Mac has his own set of folders containing documents, preferences, and other information that belongs to that user and account. If you’re the sole person who accesses your Mac, you probably have only one user. Regardless, the folder structure that OS X uses is the same whether you have one user or dozens.

If you’re the sole person who accesses your Mac, you probably have only one user. Regardless, the folder structure that OS X uses is the same whether you have one user or dozens.Within the Users folder, you find your personal Home folder (which bears your short user name), along with a Shared folder, where you can put files you want to share with other users. All these files are stored in a nested folder structure that’s a bit tricky to understand at first. This structure makes more sense after you spend a little time with it and figure out some basic concepts.

If you display the path bar at the bottom of your windows by choosing View➪Show Path Bar, it’ll start to make sense much sooner.

Take a look at Figure 6-1; you can see how these main folders are related to one another. In the sections that follow, you look at each of these folders in more depth and find out more about what’s nested inside each one.

6.1.1 Understanding nested folders

Folders within other folders are often called nested folders. To get a feel for the way nested folders work in OS X, check out Figure 6-2.

Folders within other folders are often called nested folders. To get a feel for the way nested folders work in OS X, check out Figure 6-2.You can see the following in Figure 6-2:

✓ The Desktop is the top-level folder in this example; all the other folders and files you see reside within the Desktop folder.If the preceding list makes sense to you, you’re golden. What’s important here is that you’re able to visualize the path to Folder 3. That is, to get to files inside Folder 3, you open Folder 1 and then open Folder 2 to be able to open Folder 3. Understanding this concept is important to understanding the relationships between files and folders. Keep reviewing this section, and eventually, the concept will click. You’ll slap yourself in the head and say, “Now I get it!”

✓ Folder 1 is inside the Desktop folder, which is one level deep.

✓ Folder 2 is inside Folder 1, which is one level deeper than Folder 1, or two levels deep.

✓ Folder 3 is inside Folder 2 and is three levels deep.

✓ The two files inside Folder 3 are four levels deep.

6.1.2 From the top: The Computer folder

I start with the Computer folder, which is the top level of the folder hierarchy. The Computer folder shows all the storage devices (hard drives, CD- or DVD-ROM, USB flash drive, and so forth) that are currently connected to your Mac. The following steps show how you can start at the Computer folder and drill down through the folder structure:1. To find the Computer folder, choose Go➪Computer or press Shift+⌘+C.

In Figure 6-1, the Computer folder is called Bob L’s MacBook Pro, and it contains a hard-drive icon (Mavericks HD) and a Network icon, with which you can access servers or other computers on your local network. (If that seems mysterious, read Chapter 16 for the whole scoop on sharing files with other Macs and sharing your Mac with other users.)

If you don’t see a Computer icon in your Sidebar, choose Finder➪Preferences, click the Sidebar icon at the top, and then select the check box for your computer. You can change a Mac’s name (Bob L’s MacBook Pro in Figure 6-1) in the Sharing System Preferences pane, which you can access by launching the System Preferences application (from the Applications folder, the Dock, or the • menu) and then clicking the Sharing icon. You might have more or fewer icons in your Computer folder than you see in Figure 6-1, depending on how many disks you have mounted.

2. Double-click the icon that holds your OS X stuff.

(Technically, this drive is called your boot drive.) In Figure 6-1, that hard drive is called Mavericks HD. I have no idea what yours is called, of course; if you haven’t changed it, it’s probably called Macintosh HD.

3. Check out the folders you find there.

You should see at least four folders (unless you’ve added some; if you installed the Xcode programming tools, for example, you have more). In the next few sections, I walk you through what you can find in each one.

6.1.3 Peeking into the Applications folder

You can access the Applications folder, located at the root level of your boot drive (the one with OS X installed on it), by clicking the Applications icon in the Sidebar, by choosing it in the Go menu, or by pressing Shift+⌘+A. In this folder, you find applications and utilities that Apple includes with OS X. Most users of a given Mac have access to all the items in the Applications folder, with the exception of managed accounts or accounts with Parental Controls, as discussed in Chapter 16.6.1.4 Finding fonts (and more) in the public Library folder

The Library folder, at the root level of your OS X hard drive, is like a public library; it stores items available to everyone who logs into any account on this Mac.There are actually four or more Library folders on your hard drive: one at the root level of your OS X disk, a second inside the root-level System folder, a third inside the Users folder, and the fourth in your Home folder.

What’s that you say? You don’t see a Library folder inside your Home folder? Well it’s like this: In versions of OS X earlier than OS X Lion (10.7), you would have seen a folder named Library between the Downloads and Movies folders in your Home folder (or mine — bobl — in Figure 6-1). But that was then, and this is now. In OS X Mavericks, the Home Library folder is hidden from view to protect you from yourself. You discover the secret to making it visible if you need it in the “Your personal Library card” section of this chapter, which is coming up.

Leave the /System/Library folder alone. Don’t move, remove, or rename it, or do anything within it. It’s the nerve center of your Mac. In other words, you should never have to touch this third Library folder. You find a bunch of folders inside the Library folder at root level (the “public” Library folder). Most of them contain files that you never need to open, move, or delete.

By and large, the public Library subfolder that gets the most use is the Fonts folder, which houses many of the fonts installed on the Mac. For the most part, fonts can be made available in one of two ways:

✓ To everyone who uses the Mac: If that’s the case, they’re stored here in the Fonts folder.I discuss fonts more in Chapter 14. Meanwhile, some other public Library subfolders that you might use or add to are the iMovie, iTunes, iPhoto, and iDVD folders (where you put plug-ins for those programs); the Scripts folder (which houses AppleScripts accessible to all users); and the Desktop Pictures folder (where you can place pictures to be used as Desktop backgrounds).

✓ To a single user: In this case, you place the fonts in the user’s Library folder (the one in the user’s Home folder).

Finally, the Library in the Users folder is where OS X stores configuration and preferences files shared by all users.

Don’t remove, rename, or move any files or folders in any of your Library folders unless you’re sure of what you’re doing and why. OS X is very picky about folders in its Libraries being in the proper place and bearing the proper name. While I’m on the subject, you probably shouldn’t remove,

Don’t remove, rename, or move any files or folders in any of your Library folders unless you’re sure of what you’re doing and why. OS X is very picky about folders in its Libraries being in the proper place and bearing the proper name. While I’m on the subject, you probably shouldn’t remove,rename, or move applications installed by Mavericks in the Applications folder.

Note: Under most circumstances, you won’t actually add items to or remove items from folders in this Library yourself. Software installers usually do the heavy lifting for you by placing all their little pieces in the appropriate Library folders. You shouldn’t need to touch this Library often, if ever. That said, knowing what these folders are — and who can access their contents — might come in handy down the road a piece.

The locations of all these libraries are illustrated in Figure 6-3.

If your Mac is set up for multiple users, only users with administrator (admin) privileges can put stuff in the public (root-level) Library folder. (For more information on admin privileges, check out Chapter 16.)

6.1.5 Let it be: The System folder

The System folder contains the files that OS X needs to start up and keep working.Leave the System folder alone. Don’t move, remove, or rename it or anything within it. It’s part of the nerve center of your Mac.

The bottom line is that you should, for the most part, restrict yourself to using the folders within your Home folder. If you’re the only user of your Mac, you can pretty much forget about the root level Library. But those with more than one user account on their Mac may someday need to add or remove a file from this folder.

So now you can forget everything outside your Home folder because with few exceptions, that’s where all of your “stuff” will reside.

6.1.6 The usability of the Users folder

When you open the Users folder, you see a folder for each person who has a user account on the Mac, as well as the Shared folder.The Shared folder that you see inside the Users folder allows everyone who uses the Mac to use any files stored there. If you want other people who use your Mac to have access to a file or folder, the Shared folder is the proper place to stash it. You can see the Shared folder under the MissKitty folder in Figure 6-1 earlier in this chapter.

I realize that a lot of people don’t share their Macs with others, and if you’re one of these folks, you may wonder why I keep mentioning sharing and multiple users and the like. Well, OS X is based on the Unix operating system — a multiuser operating system used on high-end servers and workstations that are often shared by several people. OS X has both the benefit of this arrangement and a bit of the confusion caused when a single user (could it be you?) fires up a computer that could be set up for several people. That’s why OS X folders are organized the way they are — with different hierarchies for each user and for the computer as a whole.

I should also mention that each user account has its own preferences and settings and that one user can’t see another user’s files by default.

If your Mac has more than one constant user, consider creating a user account for each person. If you’re a parent, separate user accounts mean you can enable Mavericks’ terrific Parental Controls, which are a very good thing if you ask me. But I’m getting ahead of myself again; Chapter 16 has the scoop on sharing your Mac and Parental Controls.

6.1.7 There’s no place like Home

From the Users folder, you can drill down into the Home folder to see what’s inside. When the user logs on to this Mac, his Home folder appears whenever he clicks the Home icon in the Sidebar, chooses Go➪Home, or uses the keyboard shortcut Shift+⌘+H.Your Home folder is the most important folder for you as a user — or at least the one where you stash most of your files. I strongly recommend that you store all the files you create in subfolders within your Home folder — preferably, in subfolders in your Home/Documents folder. The advantage of doing so is that your Home/Documents folder is easy to find, and many programs use it as the default folder for opening or saving a file.

When you open your Home folder, you see a Finder window with a little house icon and your short username in the title bar. Seeing your short username in the title bar tells you that you’re in your Home folder. Every user has a Home folder named after his or her short username (as specified in the Users & Groups System Preferences pane). Figure 6-4 shows that my Home folder is named bobl — the short name I used when I first set up my Mac.

When you open your Home folder, you see a Finder window with a little house icon and your short username in the title bar. Seeing your short username in the title bar tells you that you’re in your Home folder. Every user has a Home folder named after his or her short username (as specified in the Users & Groups System Preferences pane). Figure 6-4 shows that my Home folder is named bobl — the short name I used when I first set up my Mac.If your Mac has more than one user, you can see the other users’ Home folders in your Users folder, but OS X prevents you from opening files from or saving files to them.

By default, your Home folder has several folders inside it created by OS X. The following four are the most important:

✓ Desktop: If you put items (files, folders, applications, or aliases) on the Desktop, they’re actually stored in the Desktop folder.You can create more folders, if you like. In fact, every folder that you ever create (at least every one you create on this particular hard drive or volume) should be within your Home folder. I explain more about creating folders and subfolders and organizing your stuff inside them later in this chapter.

✓ Documents: This is the place to put all the documents (letters, spreadsheets, recipes, and novels) that you create.

✓ Library: As I mention earlier in this chapter, this Library folder is invisible in Mavericks; I show you how to deal with that shortly. Rest assured that even though it’s hidden, it’s still one of the most important folders in your Home folder, containing Preferences (files containing the settings you create in System Preferences and other places), fonts available only to you (as described earlier in this chapter), and other stuff that you — and only you — expect to use.

✓ Public: If others on your local area network use file sharing to connect with your Mac, they can’t see or use the files or folders in your Home folder (unless you’ve explicitly shared them), but they can share files you’ve stored in your Home folder’s Public folder. (Read more about file sharing and Public folders in Chapter 16.)

The following are a few more tidbits to keep in mind as you dig around your Home folder:

✓ If you decide that you don’t want an item on the Desktop anymore, delete it by dragging its icon from the Desktop folder to the Trash or by dragging its icon from the Desktop itself to the Trash. Both techniques yield the same effect: The file is in the Trash, where it remains until you empty the Trash. Or if you don’t want it on the Desktop anymore but don’t want to get rid of it either, you can drag it from the Desktop into any other folder you like.

✓ The other four folders that you should see in your Home folder are Downloads, Movies, Music, and Pictures. All these folders except Downloads are empty until you (or a program such as iTunes, GarageBand, iPhoto, or iMovie, which create files inside these folders automatically the first time you launch them) put something in these folders. And the Downloads folder might as well be empty, but it contains a document entitled, About Downloads, with a little info on Dock stacks and the Downloads folder and concludes by saying, “. . . when you’re done reading this document, feel free to throw it out.”

6.1.8 Your personal Library card

The invisible Library subfolder of your Home folder is the repository of everything that OS X needs to customize your Mac to your tastes. If you want to add something to a Library folder, it’s usually best to add it to your Home/Library folder. You won’t spend much time (if any) adding things to the Library folder or moving them around within it, and that’s probably why it’s now hidden from sight. Still, I think it’s a good idea for you to know what’s in your Home/Library.In the “Finding fonts (and more) in the public Library folder” section, earlier in this chapter, I discuss the Library folder that’s used to specify preferences for the Mac as a whole. But this Library folder is all about you and your stuff.

Be cautious with all Library folders. OS X is very persnickety about how the folders and files within it are organized. As I discuss earlier in the chapter, you can add items to and remove items safely from most public or Home Library folders, but leave the folders themselves alone. If you remove or rename the wrong folder, you could render OS X inoperable. It’s like the old joke about the guy who said to the doctor, “It hurts when I do that,” and the doctor replies, “Then don’t do that.”

To find your hidden Home/Library folder, do this:

You should see several folders in the Home/Library folder; the exact number depends on the software that you install on your Mac. You probably have folders called Mail, Safari, Logs, and Preferences, for example.1. Hold down the Option key on your keyboard.

2. Click the Go menu.

The (formerly) invisible Library folder appears in the Go menu as long as the Option key is pressed, as shown in Figure 6-5.

3. Select Library and release the mouse button.

If you don’t want to have to do this dance every time you want to open your Home/Library, Mavericks has a new option for you: There’s now a Show Library Folder check box in the View Options window (choose View➪Show/Hide View Options or press ⌘+J). Select it, and your Home/Library will be visible evermore (or at least until you deselect the check box).

Some of the most important standard folders in the Library folder include the following:

✓ Application Support: Some applications store their support files here; others store theirs in the main (root-level) public Library folder.

✓ Fonts: This folder is empty until you install your own fonts here. The fonts that come with OS X aren’t stored here, but in the Library folder at root level for everyone who uses this Mac. I discuss this topic earlier in this chapter. If you want to install fonts so that only you have access to them, put them in the Fonts folder in your Library folder.

The easiest way to install a font is to double-click its icon and let Mavericks’ Font Book utility handle it for you, as described in Chapter 14. But I’d be remiss if I didn’t also mention how to install a font manually:

• To install a font that only you can use: Drag the font file’s icon to the Fonts folder in your Home/Library. The font is available only to this user account (because other users can’t use fonts stored in your Home/Library folder).✓ Preferences: The files here hold the information about whichever things you customize in OS X or in the applications you run. Whenever you change a system or application preference, that info is saved to a file in the Preferences folder.

• To install a font for all users of this Mac: Drag the font file’s icon into the Fonts folder in the public Library folder — the one at root level that you see when you open your hard drive’s icon.

Don’t mess with the Preferences folder! You should never need to open or use this folder unless something bad happens — if, for example, you suspect that a particular preferences file has become corrupted (that is, damaged). My advice is to just forget that you know about this folder and let it do its job. If you don’t know why you’re doing something to a folder (other than the Fonts folder) in your Home/Library, don’t do it. There must be some good reasons why Apple decided to hide the Home/Library folder in OS X Mavericks, and I’m sure that one of them is to keep you (or me) from accidentally screwing something up.

6.2 Saving Your Document Before It’s Too Late

If you have a feel for the OS X folder structure, you can get down to the important stuff — namely, how to save documents and where to save them. You can create as many documents as you want, using one program or dozens of ’em, but all could be lost if you don’t save the files (or versions of the files) to a storage device such as your hard drive or other disk.When you save a file, you’re committing a copy to a disk — whether it’s a disk connected directly to your Mac, one available over a network, or a removable disk such as a USB flash drive or portable hard disk.

Lion introduced three new features — Resume, Auto Save, and Versions — to make your life easier. In previous versions of OS X, applications generally showed a blank page or nothing at all when you launched them. Mavericks’ Resume feature automatically reopens all windows that were onscreen when you quit the app. So, when you launch the app again, all the windows are reopened in the same position onscreen as when you quit. Best of all, Resume seems to work with most third-party apps.

Programs have offered Auto Save before, but now it’s baked into OS X. Auto Save automatically saves versions of your work as you work, when you pause, and every five minutes, whether you need it or not.

For as long as we’ve had Macs, we’ve saved unique versions of our files, creating and managing them with the Save As command or by duplicating and renaming them in the Finder. Now Mavericks (like Lion and Mountain Lion before it) takes over version control for you by automatically saving versions as described in the preceding paragraph.

That’s the good news, but there’s also bad news . . . although Auto Save and versions are baked right into OS X, third-party apps require a software update before they can take advantage of these features. So please don’t get too comfortable with Auto Save and Versions until you’re sure that your applications take advantage of these features. Most third-party apps still rely on the good old Save and Save As commands, which have been around since time immemorial (or at least since 1984).

In the following sections, I show you how to save your masterpieces. Prevent unnecessary pain in your life by developing good saving habits. I recommend that you save your work (or save a version in apps that support versions)

✓ Every few minutesThe keyboard shortcut for Save in almost every Mac program is ⌘+S. Memorize it. See it in your dreams. Train your finger muscles to do it unconsciously. Use it (the keyboard shortcut) or lose it (your unsaved work).

✓ Before you switch to another program

✓ Before you print a document

✓ Before you stand up

If you don’t heed this advice — and the program that you’re using crashes while switching programs, printing, or sitting idle (the three likeliest times for a crash) — you may lose everything you did since your last save or saved version. The fact that a program crash doesn’t bring down the entire system or force a restart is small consolation when you’ve lost everything you’ve typed, drawn, copied, pasted, or whatever since the last time you saved or saved a version.

6.2.1 Stepping through a basic Save

This section walks you through the steps you use the first time you save a document. The process is the same whether your app supports Auto Save and Versions or not. It’s only after the initial save that Auto Save and Versions come into play.In a few sections of this book, I ask you not only to read the instructions while sitting in front of your Mac but also to perform each step of the instructions as described. This section is one of them. If you read it and follow along, I can pretty much guarantee that it’ll make sense. If you read it somewhere other than at your Mac, it could be a mite confusing.

Saving a file works pretty much the same way in any application you use to create documents. For this example, I use OS X’s word processing application, TextEdit, but the process will be very similar in Microsoft Word, Adobe Photoshop, Apple Keynote, or any other application.

If you’re going to follow along as I recommend, please launch the TextEdit program now (it’s in your Applications folder), click the New Document button or choose File➪New, and type a few words on the Untitled page that appears after you launch it.

Now that we’re both on the same page, both literally and figuratively, here’s how saving a file works: When you choose to save a file for the first time (by choosing File➪Save or pressing ⌘+S), a Save sheet appears in front of the document that you’re saving, as shown in Figure 6-6. I call this a basic Save sheet (as opposed to an expanded Save sheet, which I get to in a moment):

1. In the Save As field, type a name for your file.

When a Save sheet appears for the first time, the Save As field is active and displays the name of the document. The document name (usually, Untitled) is selected; when you begin typing, the name disappears and is replaced by the name you type.2. If the Where pop-up menu lists the location where you want to save your file, choose that location and proceed to Step 5; if not, click the disclosure button (the one with the little triangle to the right of the word Untitled in Figure 6-6).

You can choose from a short list of folders and volumes listed in the basic Save sheet’s Where pop-up menu (which are the same devices and favorites you see in the Sidebar of Finder windows). Or, if you click the disclosure button (triangle), the sheet expands so that you can navigate folders just as you do in the Finder: by opening them to see their contents.

After you’ve saved a file for the first time, choosing File➪Save or pressing ⌘+S won’t bring up a Save sheet. Instead, what happens next depends on whether the app supports Mavericks’ Auto Save and Versions. If the app doesn’t support Auto Save and Versions, Save and its shortcut, ⌘+S, merely resave your document in the same location and with the same name. If you want to save a unique version with a different name you choose the Save As command and save the file under a new name. If the app does support Auto Save and Versions, however, the upcoming section, “Save As versus Duplicate: Different names for the same result,” explains how things work.

If you clicked the Save button instead of pulling down the Where menu, your file will be saved to iCloud, Apple’s free online storage service (which you discover in Chapter 10).3. To find the folder where you want to save your file, choose among views by clicking the Icon, List, Column, or Cover Flow view button.

If you switch to expanded view by clicking the disclosure button, the Where pop-up menu shows the path to the folder the file will be saved in (Documents in Figure 6-6 and Figure 6-7).

I think that the Where menu should be the same in both basic and expanded Save sheets, as it was before OS X 10.5 Leopard. It seems more confusing to have the contents of this menu change based on whether the Save sheet is expanded or not. I’ve called it to your attention so it won’t confuse you.

Switch between the basic and expanded Save sheets a few times by clicking the disclosure button. Make sure that you see and understand the difference between what you see in the Where menu in a basic Save sheet and what you see in the Where menu in an expanded Save sheet.

(The buttons look like their counterparts in Finder windows.) In icon view, you double-click a folder to open it. List and Cover Flow views offer disclosure triangles for folders and disks, so single-click the disclosure triangles of folders to see their contents. In column view, you click an item on the left to see its contents on the right, just as you do in a column-view Finder window.4. Select the folder where you want to save your file in the Where pop-up menu or Sidebar.

You can also use the Forward and Back buttons or the Sidebar, both available only in an expanded Save dialog, to conveniently navigate your disk. Many of these navigation aids work just like the ones in the Finder; flip back to Chapter 5 for more details. You can enlarge the Save sheet to see more the same way you enlarge a Finder window: Drag an edge or corner of the sheet.

If you can’t find the folder in which you want to save your document, type the folder’s name in the Search box. It works just like the Search box in a Finder window, as described in Chapter 5. You don’t even have to press Enter or Return; the Save sheet updates itself to show you only items that match the characters as you’ve typed them.

5. If you want to create a new subfolder of the selected folder to save your file in, click the New Folder button, give the new folder a name, and then save your file in it.

6. In the File Format pop-up menu, make sure the format selected is the one you want.In Figure 6-8, I’ve selected an existing folder named Novels. You can tell that it’s selected because its name is displayed in the Where menu and highlighted below that in the first column.

The selected folder is where your file will be saved.

The keyboard shortcut for New Folder is Shift+⌘+N, regardless of whether you’re in a Save sheet or the Finder. If I’d wanted to create a new folder inside the Novels folder in Figure 6-8, I could have clicked the New Folder button or pressed the shortcut.

7. If you want to turn off the display of file extensions (such as .rtf, .pdf, and .txt) in Save sheets, select the Hide Extension check box.

8. Double-check the Where pop-up menu one last time to make sure that the correct folder is selected; then click the Save button to save the file to the active folder.

If you click Save, the file appears in the folder you selected. If you change your mind about saving this file, clicking Cancel dismisses the Save sheet without saving anything anywhere. In other words, the Cancel button returns things to the way they were before you displayed the Save sheet.

When you use apps that don’t support Auto Save and Versions, I beg you to get into the habit of pressing ⌘+S often. It can’t hurt — and just might save your bacon someday.

One last thing: In Figures 6-6, 6-7, and 6-8, I used the Save sheet for TextEdit as an example. In programs other than TextEdit, the Save sheet might contain additional options, fewer options, or different options, and therefore may look slightly different. The File Format menu, for example, is a feature specific to TextEdit; it might not appear in other applications’ Save sheets. Don’t worry. The Save sheet always works the same way, no matter what options it offers.

6.2.2 Save As versus Duplicate: Different names for same result

File➪Duplicate and File➪Save As serve the same purpose and achieve the same result. The difference is that you’ll find File➪Duplicate in apps that support Versions and Auto Save, and File➪Save As in apps that don’t. They’re different names for achieving the same result: Saving a file that’s already been saved with a different name, with the option of saving the renamed file in a different folder.Before I get into the details, you may be wondering why you would want to save an existing file with a different name. So here’s a good (albeit kind of rude) example: Suppose that you have two cousins, Kate and Nancy. You write Kate a long, chatty letter and save this document with the name Letter to Kate. Later, you decide that you want to send almost the same letter to Nancy, but you want to change a few things. So you change the part about your date last night and replace all references to Kate’s husband, Kevin, with references to Nancy’s husband, Norman. (Aren’t computers grand?)

So you make all these changes in Letter to Kate, but you haven’t resaved this document yet, and although the document on your screen is actually a letter to Nancy, its filename is still Letter to Kate. Think of what would happen if you were to save it now without using the Save As feature: Letter to Kate reflects the changes that you just made. (The stuff in the letter meant for Kate is blown away, replaced by the stuff that you just wrote to Nancy.) Thus the filename Letter to Kate is inaccurate. Even worse, you might no longer have a copy of the original letter you sent to Kate! The solution? Just use Save As or Duplicate to rename this file Letter to Nancy by choosing File➪Save As or File➪Duplicate.

If you chose Save As: A Save sheet appears, in which you can type a different filename in the Save As field. You can also navigate to another folder, if you like, and save the newly named version of the file there. Now you have two distinct files: Letter to Kate and Letter to Nancy. Both contain the stuff they should, but both started life from the same file.

If you chose Duplicate: The title bar of the document becomes editable so you can change its name without even seeing a Save sheet. (Refer to the figure in the earlier sidebar, “Does it have Auto Save and Versions or not?”) Press Enter or Return, and the renamed file will be saved in the same folder as the original. Or, if you want to save the newly renamed file in a different location, choose File➪Move To or click the little triangle to the right of the document’s name, choose Move To in its pop-up menu, and then from the pop-up menu, select a folder in which to save the file.

Now that you understand what Save As or Duplicate are all about, here’s an easier way to get the same result: Before you start, duplicate the document in the Finder (choose File➪Duplicate or press ⌘+D). Rename the copy and open it. This way, when you’re done making changes, you don’t have to remember to choose Save As; you can just perform your habitual Save. This approach also protects you from accidentally saving part of the letter to Nancy without changing the file’s name first (which you’re likely to do if you’re following my advice about saving often). So when you decide that you’re going to reuse a document, choose Save As (or duplicate and rename the file) before you begin working on it, just to be safe.

Versions gives you the benefits of Save As without any action on your part, many programs still lack support for Auto Save and Versions at press time. And, in fact, some of Apple’s apps, as well as most third-party apps, still use the Save As technique, and I expect that to be the status quo for quite some time. But since some of Apple’s offerings (most notably TextEdit) use Auto Save and Versions, I’d be remiss if I glossed over the new way of doing things.

One last thing: If the app you’re using supports Mavericks’ Versions, it creates a snapshot called a Version automatically as you work, when you pause, every five minutes, and every time you choose File➪Save (⌘+S). Choose File➪Revert To➪Browse All Versions to compare different versions of the document you’ve saved side-by-side, as shown in Figure 6-9.

Figure 6-9 is actually Mavericks’ Time Machine backup utility displaying the various Versions. Read more about Time Machine in Chapter 18.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий