6.3 Open Sez Me

You can open any icon in the Finder — whether it’s a file or a folder — in at least six ways. (Okay, there are at least seven ways, but one of them belongs to aliases, which I discuss in great detail back in Chapter 5.) Anyway, here are the ways:✓ Click the icon once to select it and choose File➪Open.You can also open any document icon from within an application, of course. Here’s how that works:

✓ Click the icon twice in rapid succession.

If the icon doesn’t open, you double-clicked too slowly. You can test (and adjust) your mouse’s sensitivity to double-click speed in the Mouse (or Trackpad) System Preference pane, which you can access by launching the System Preferences application (from the Applications folder, the Dock, or the • menu) and then clicking the Mouse (or Trackpad) icon.✓ Select the icon and then press either ⌘+O or ⌘+↓.

✓ Right-click or Control-click it and then choose Open from the contextual menu.

✓ If the icon is a document, drag it onto the application icon (or the Dock icon of an application) that can open that type of document.

✓ If the icon is a document, right-click or Control-click it and choose an application from the Open With submenu of the contextual menu.

1. Just launch your favorite program, and choose File➪Open (or press ⌘+O, which works in most Mac programs).For what it’s worth, some applications allow you to select multiple files in their Open dialogs by holding down either Shift (for contiguous selections) or ⌘ (for noncontiguous selections). If you need to open several files, it’s worth a try; the worst thing that could happen is that it won’t work and you’ll have to open the items one at a time.

2. In the dialog, simply navigate to the file you want to open (using the same techniques you use in a Save sheet).An Open dialog appears, like the one shown in Figure 6-10.

When you use a program’s Open dialog, only files that the program knows how to open appear enabled (in black rather than light gray) in the file list. In effect, the program filters out the files it can’t open, so you barely see them in the Open dialog. This method of selectively displaying certain items in Open dialogs is a feature of most applications. Therefore, when you’re using TextEdit, its Open dialog dims all your spreadsheet files (because TextEdit can open only text, Rich Text Format, Microsoft Word, and some picture files). Pretty neat, eh?

Click a favorite folder in the Sidebar or use Spotlight if you can’t remember where the file resides.3. Select your file and click the Open button.

Some programs, including Microsoft Word and Adobe Photoshop, have a Show or Format menu in their Open dialogs. This menu lets you specify the type(s) of files you want to see as available in the Open dialog. You can often open a file that appears dimmed by choosing All Documents from the Show or Format menu (in those applications with Open dialogs that offer such a menu).

6.3.1 With drag-and-drop

Macintosh drag-and-drop is usually all about dragging text and graphics from one place to another. But there’s another angle to drag-and-drop — one that has to do with files and icons.You can open a document by dragging its icon onto that of the proper application. You can open a document created with Microsoft Word, for example, by dragging the document icon onto the Microsoft Word application’s icon. The Word icon highlights, and the document launches. Usually, of course, it’s easier to double-click a document’s icon to open it; the proper application opens automatically when you do — or at least, it does most of the time. Which reminds me . . .

6.3.2 With a Quick Look

To use the Quick Look command to peek at the contents of most files in Open dialogs, right-click or Control-click the file and choose Quick Look, or use its easy-to-remember shortcut: Press the spacebar. Whichever way, you’ll soon see the contents of that file in a floating window without launching another application.

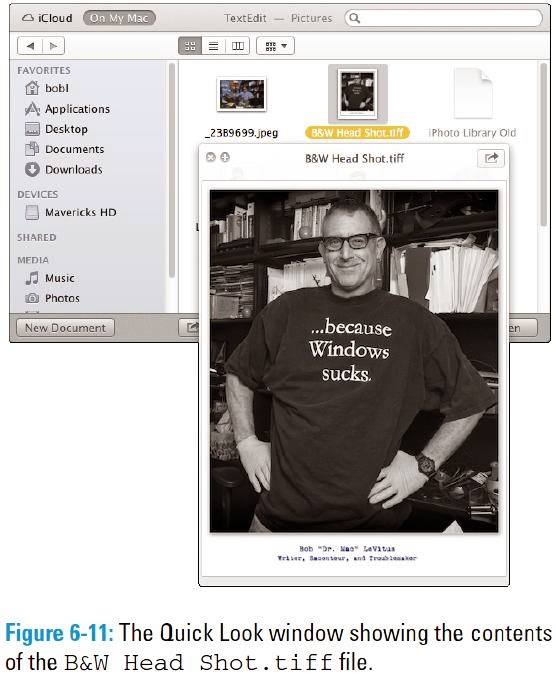

To use the Quick Look command to peek at the contents of most files in Open dialogs, right-click or Control-click the file and choose Quick Look, or use its easy-to-remember shortcut: Press the spacebar. Whichever way, you’ll soon see the contents of that file in a floating window without launching another application.The Quick Look window, shown in Figure 6-11, shows you the contents of many types of files.

Sometimes Quick Look even works on files the current application can’t open. For the most part, if a file can be selected in an Open dialog, you can probably view its contents with Quick Look. Quick Look is so wonderful it’s also available for icons in the Finder. But you’ll have to wait for Chapter 7 to read about the rest of Quick Look’s charms.

6.3.3 When your Mac can’t open a file

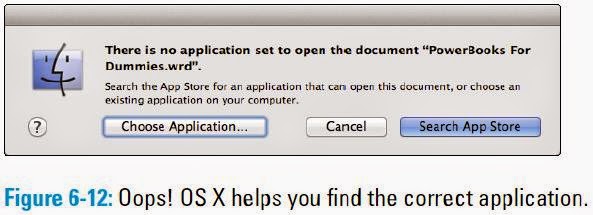

If you try to open a file, but OS X can’t find a program to open that file, OS X prompts you with an alert window. I tried to open a very old (1993) file created on a long-defunct Psion Series 3 handheld PDA — a file so old that most of you have probably never seen the .wrd file extension, shown in Figure 6-12.

If you try to open a file, but OS X can’t find a program to open that file, OS X prompts you with an alert window. I tried to open a very old (1993) file created on a long-defunct Psion Series 3 handheld PDA — a file so old that most of you have probably never seen the .wrd file extension, shown in Figure 6-12.Click Cancel to abort the attempt to open the file, or click the Choose Application or Search App Store button to select another application to open this file.

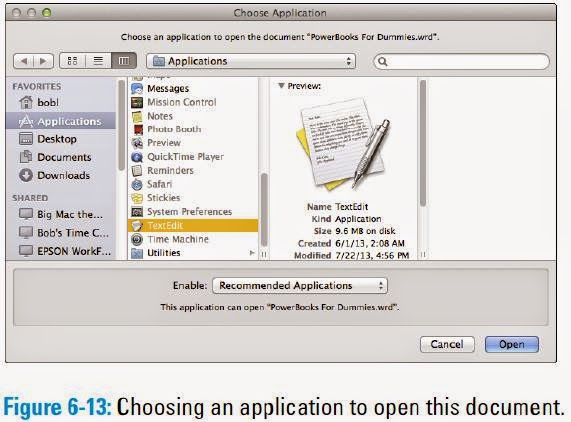

If you click the Choose Application button, a dialog appears (conveniently opened to your Applications folder and shown in Figure 6-13). Applications that OS X doesn’t think can be used to open the file are dimmed. For a wider choice of applications, choose All Applications (instead of Recommended Applications) from the Enable pop-up menu.

If you click the Choose Application button, a dialog appears (conveniently opened to your Applications folder and shown in Figure 6-13). Applications that OS X doesn’t think can be used to open the file are dimmed. For a wider choice of applications, choose All Applications (instead of Recommended Applications) from the Enable pop-up menu.You can’t open every file with every program. If you try to open an MP3 (audio) file with Microsoft Excel (a spreadsheet), for example, it just won’t work; you get an error message or a screen full of gibberish. Sometimes, you just have to keep trying until you find the right program; at other times, you don’t have a program that can open the file.

When in doubt, Google the file extension. You’ll usually find out more than you need to know about what application(s) create files with that extension.

6.3.4 With the application of your choice

I don’t know about you, but people send me files all the time that were created by applications I don’t use . . . or at least that I don’t use for that document type. OS X lets you specify the application in which you want to open a document in the future when you double-click it. More than that, you can specify that you want all documents of that type to open with the specified application. “Where is this magic bullet hidden?” you ask. Right there in the file’s Info window.6.3.4.1 Assigning a file type to an application

Suppose that you want all .jpg files that usually open in Preview to open instead in Acorn, a more capable third-party image-editing program. Here’s what to do:1. Click one of the files in the Finder.

2. Choose File➪Get Info (⌘+I).

3. In the Info window, click the gray triangle to disclose the Open With pane.

4. From the pop-up menu, choose an application that OS X believes will open this document type.

5. (Optional) If you click the Change All button at the bottom of the Open With pane, as shown on the right side of Figure 6-14, you make Acorn the new default application for all .jpg files that would otherwise be opened in Preview.In Figure 6-14, I’m choosing Acorn. Now Acorn opens when I open this file (instead of the default application, Preview).

Notice the handy alert that appears when you click the Change All button and how nicely it explains what will happen if you click Continue.

6.3.4.2 Opening a file with an application other than the default

Here’s one more technique that works great when you want to open a document with a program other than its default. Just drag the file onto the application’s icon or alias icon or Dock icon, and presto — the file opens in the application.If I were to double-click an MP3 file, for example, the file usually would open in iTunes (and, by default, would be copied into my iTunes Library). But I frequently want to audition (listen to) MP3 files with QuickTime Player, so they’re not automatically added to my iTunes music library. Dragging the MP3 file onto QuickTime Player’s icon in the Applications folder or its Dock icon (if it’s in the Dock) solves this conundrum quickly and easily.

If the icon doesn’t highlight and you release the mouse button anyway, the file ends up in the same folder as the application with the icon that didn’t highlight. If that happens, just choose Edit➪Undo (or press ⌘+Z), and the mislaid file magically returns to where it was before you dropped it. Just remember — don’t do anything else after you drop the file, or Undo might not work. If Undo doesn’t work, you must move the file back to its original location manually.

Only applications that might be able to open the file should highlight when you drag the file on them. That doesn’t mean the document will be usable — just that the application can open it. Suffice it to say that OS X is usually smart enough to figure out which applications on your hard drive can open what documents — and to offer you a choice.

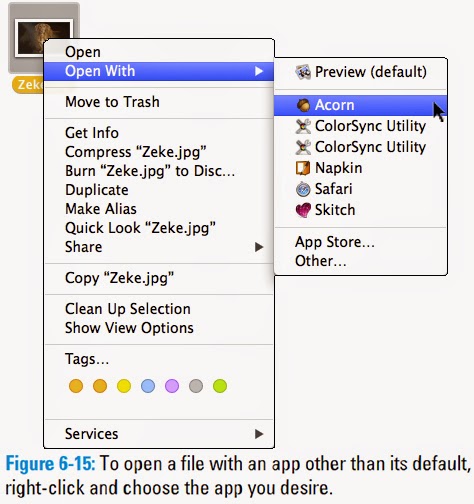

Only applications that might be able to open the file should highlight when you drag the file on them. That doesn’t mean the document will be usable — just that the application can open it. Suffice it to say that OS X is usually smart enough to figure out which applications on your hard drive can open what documents — and to offer you a choice.One last thing: If all you want to do is open a file with an application other than its default (and not change anything for the future), the techniques I’ve just described work fine, but the easiest way is to right-click the file and choose another app from the pop-up menu, as shown in Figure 6-15.

You can also change the default application to open this file by pressing Option after you right-click the file, and the Open With command will magically transform into Always Open With. Alas, you can’t change the default application for all files of this type (.jpg in Figures 6-14 and 6-15); for that you’ll have to visit the Info window.

6.4 Organizing Your Stuff in Folders

I won’t pretend to be able to organize your Mac for you. Organizing your files is as personal as your taste in music; you develop your own style with the Mac. But after you know how to open and save documents when you’re using applications, these sections provide food for thought — some ideas about how I organize things — and some suggestions that can make organization easier for you, regardless of how you choose to do it.The upcoming sections look at the difference between a file and a folder; show you how to set up nested folders; and cover how some special folder features work. After you have a good handle on these things, you’ll almost certainly be a savvier — and better organized — OS X user.

6.4.1 Files versus folders

When I speak of a file, I’m talking about what’s connected to any icon except a folder or disk icon. A file can be a document, an application, an alias of a file or an application, a dictionary, a font, or any other icon that isn’t a folder or disk. The main distinction is that you can’t put something in most file icons.The exceptions are icons that represent OS X packages. A package is an icon that acts like a file but isn’t. Examples of icons that are really packages include many software installers and applications, as well as “documents” saved by some programs (such as Keynote, GarageBand, or TextEdit files saved in its .rtfd format). When you open an icon that represents a package in the usual way (double-click, choose File➪Open, press ⌘+O, and so on), the program or document opens. If you want to see the contents of an icon that represents a package, you have to right-click or Control-click the icon first and choose Show Package Contents from the contextual menu. If you see an item by that name, you know that the icon is a package; if you don’t see Show Package Contents on the contextual menu, the icon represents a file, not a package.

When I talk about folders, I’m talking about things that work like manila folders in the real world. Their icons look like folders, like the one in the margin to the left; they can contain files or other folders, called subfolders. You can put any icon — any file or folder — inside a folder.

Here’s an exception: If you try to put a disk icon in a folder, all you get is an alias to the disk unless you hold down the Option key. Remember that you can’t put a disk icon in a folder that exists on the disk itself. In other words, you can copy a disk icon only to a different disk; you can never copy a disk icon to a folder that resides on that disk. For more about aliases, flip to Chapter 5; for details on working with disks, see Chapter 8.

File icons can look like practically anything. If the icon doesn’t look like a folder, package, or one of the numerous disk icons, you can be pretty sure that it’s a file.

6.4.2 Organizing your stuff with subfolders

As I mention earlier in this chapter, you can put folders inside other folders to organize your icons. A folder “nested” inside another folder is called a subfolder.You can create subfolders according to whatever system makes sense to you — but why reinvent the wheel? Here are some organizational topic ideas and naming examples for subfolders:

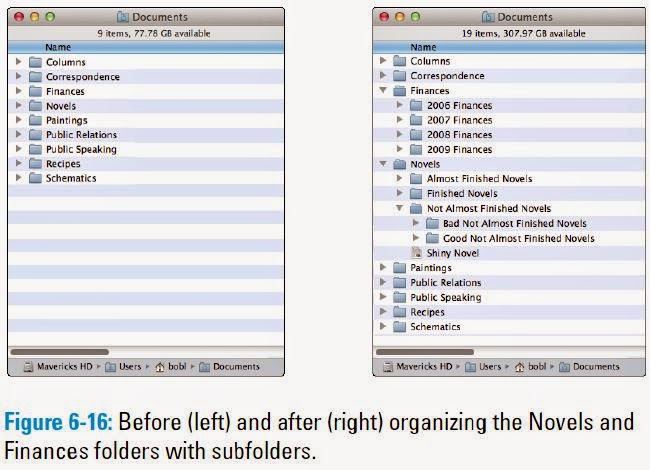

✓ By type of document: Word-Processing Documents, Spreadsheet Documents, Graphics DocumentsWhen you notice your folders swelling and starting to get messy (that is, filling with tons of files), subdivide them again by using a combination of these methods that makes sense to you. Suppose that you start by subdividing your Documents folder into multiple subfolders. Later, when those folders begin to get full, you can subdivide them even further, as shown in Figure 6-16.

✓ By date: Documents May–June, Documents Spring ’12

✓ By content: Memos, Outgoing Letters, Expense Reports

✓ By project: Project X, Project Y, Project Z

My point (yes, I do have one!): Allow your folder structure to be organic, growing as you need it to grow. Let it happen. Don’t let any single folder get so full that it’s a hassle to deal with. Create new subfolders when things start to get crowded. (I explain how to create folders in the next section.)

My point (yes, I do have one!): Allow your folder structure to be organic, growing as you need it to grow. Let it happen. Don’t let any single folder get so full that it’s a hassle to deal with. Create new subfolders when things start to get crowded. (I explain how to create folders in the next section.)If you want to monkey around with some subfolders, a good place to start is the Documents folder, which is inside your Home folder (that is, the Documents folder is a subfolder of your Home folder).

If you use a particular folder a great deal, put it in your Dock, or make an alias of it and move the alias from the Documents folder to your Home folder or to your Desktop (for more info on aliases, see Chapter 5) to make the folder easier to access. Or drag the folder (or its alias) to the Sidebar, so it’s always available, including in Open dialogs and Save sheets. If you write a lot of letters, keep an alias to your Correspondence folder in your Home folder, in the Dock, on your Desktop, or in the Sidebar for quick access. (By the way, there’s no reason why you can’t have a folder appear in all four places, if you like. That’s what aliases are for, right?)

If you create your own subfolders in the Documents folder, you can click that folder in the Dock to reveal them, as shown in Figure 6-17. I show you how to customize the Dock in Chapter 4.

It’s even more convenient if you choose to view the Documents folder as a list, as described in Chapter 4 and shown in Figure 6-17!

6.4.3 Creating new folders

So you think that Apple has already given you enough folders? Can’t imagine why you’d need more? Think of creating new folders the same way you’d think of labeling a new folder at work for a specific project. New folders help you keep your files organized, enabling you to reorganize them just the way you want. Creating folders is really quite simple.To create a new folder, just follow these steps:

1. Decide which window you want the new folder to appear in — and then make sure that window is active.

If you want to create a new folder right on the Desktop, make sure that no window is active or that you’re working within your Home/Desktop folder window. You can make a window active by clicking it, and you can make the Desktop active if you have windows onscreen by clicking the Desktop itself.2. Choose File➪New Folder (or press Shift+⌘+N).

A new, untitled folder appears in the active window with its name box3. Type a name for your folder.

already highlighted, ready for you to type a new name for it.

If you accidentally click anywhere before you type a name for the folder,

the name box is no longer highlighted. To highlight it again, select the icon (single-click it) and press Return (or Enter) once. Now you can type its new name.

Give your folders relevant names. Folders with nebulous titles like sfdghb or Stuff or Untitled won’t make it any easier to find something six months from now.

For folders and files that you might share with users of non-Macintosh computers, here’s the rule for maximum compatibility: Use no punctuation and no Option-key characters in the folder name. Periods, slashes, backslashes, and colons in particular can be reserved for use by other operating systems. When I say Option-key characters, I’m talking about special-purpose ones such as ™ (Option+2), ® (Option+R), ¢ (Option+4), and even © (Option+G).

6.4.4 Navigating with spring-loaded folders

A spring-loaded folder pops open when you drag something onto it without releasing the mouse button. Spring-loaded folders work with all folder or disk icons in all views and in the Sidebar. Because you just got the short course on folders, subfolders, and various ways to organize your stuff, you’re ready for your introduction to one of my favorite ways to get around my disks, folders, and subfolders.Here’s how spring-loaded folders work:

1. Select any icon except a disk icon.After you get used to spring-loaded folders, you’ll wonder how you ever got along without them. They work in all four views, and they work with icons in the Sidebar or Dock. Give ’em a try, and you’ll be hooked. You can toggle spring-loaded folders on or off in the Finder’s Preferences window. There’s also a setting for how long the Finder waits before it springs the folders open. See Chapter 5 for more on Finder preferences.

The folder highlights to indicate that it’s selected.2. Drag the selected icon onto any folder or disk icon — but don’t release the mouse button.

• I call this hovering because you’re doing just that: hovering the cursor over a folder or disk icon without releasing the button.3. After the folder springs open, perform any of these handy operations:

• In a second or two, the highlighted folder or disk flashes twice and then springs open, right under the cursor.

• Press the spacebar to make the folder spring open immediately.

• Continue to traverse your folder structure this way. Subfolders continue to pop open until you release the mouse button.

• If you release the mouse button, the icon you’ve been dragging is dropped into the active folder at the time. That window remains open — but all the windows you traversed clean up after themselves by closing automatically, leaving your window clean and uncluttered.

• If you want to cancel a spring-loaded folder, drag the cursor away from the folder icon or outside the boundaries of the sprung window. The folder pops shut.

6.4.5 Smart Folders

As the late Steve Jobs was fond of saying near the end of his keynotes, “There is one more thing,” and when it comes to folders, that one last thing is the Smart Folder. A Smart Folder lets you save search criteria and have them work in the background to display the results in real time. In other words, a Smart Folder is updated continuously, so it displays all the files on your computer that match the search criteria at the moment.

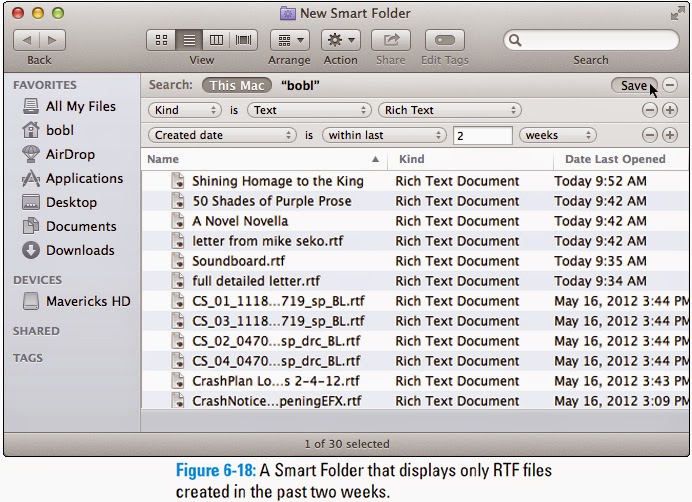

A Smart Folder lets you save search criteria and have them work in the background to display the results in real time. In other words, a Smart Folder is updated continuously, so it displays all the files on your computer that match the search criteria at the moment.So, for example, say you create a Smart Folder that contains all the Rich Text Format files on your computer that you’ve opened in the past two weeks, as shown in Figure 6-18. Or you can create a Smart Folder that displays graphics files, but only the ones bigger (or smaller) than a specified file size. Then all those files appear in one convenient Smart Folder.

The possibilities are endless. Because Smart Folders use aliaslike technology to display items, the actual files reside in only one location: the folder where you originally put them. True to their name, Smart Folders don’t gather the files themselves in a separate place; rather, they gather aliases of files, leaving the originals right where you stashed them. Neat!

Also, because Spotlight (discussed in Chapter 7) is built deep into the bowels of the OS X file system and kernel, Smart Folders are updated in real time and so are always current, even after you’ve added or deleted files on your hard drive since creating the Smart Folder.

Smart Folders are so useful that Apple provides five ways to create one. The following steps show you how:

1. Start your Smart Folder by using any of the following methods:

• Choose File➪New Smart Folder.2. Refine the criteria for your search by clicking the + button to add a criterion or the – button to delete one.

• Press ⌘+Option+N.

• Choose File➪Find.

• Press ⌘+F.

• Type at least one character in the Search box of a Finder window.

If you have All My Files selected in the Sidebar, you can’t use the last method, because All My Files is a Smart Folder — one with a weird icon, but a Smart Folder nonetheless.

3. When you’re satisfied and ready to turn your criteria into a Smart Folder, click the Save button below the Search box.

A sheet drops down.4. Choose where you want to save your folder.

While the Save sheet is displayed, you can add the Smart Folder to the Sidebar, if you like, by clicking the Add to Sidebar check box.5. When you’re finished editing criteria, click the Save button to save the folder with its criteria.

After you create your Smart Folder, you can save it anywhere on any hard drive and use it like any other folder. There’s also an option to display it in your Sidebar, if you want.

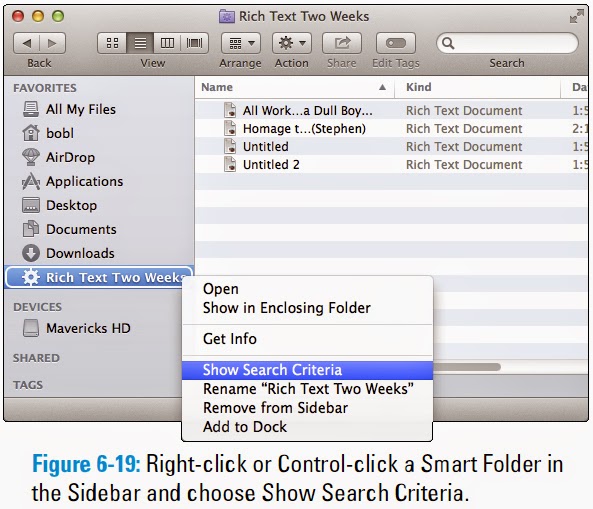

After you create your Smart Folder, you can save it anywhere on any hard drive and use it like any other folder. There’s also an option to display it in your Sidebar, if you want.If you want to change the criteria for a Smart Folder you created earlier, right-click or Control-click the Smart Folder in the Sidebar and select Show Search Criteria, as shown in Figure 6-19.

Alternatively, you can right-click or Control-click the Smart Folder (even one in the Sidebar) and choose Show Search Criteria from the contextual menu.

When you’re finished changing the criteria, click the Save button to resave your folder. Don’t worry — if you try to close a Smart Folder you’ve modified without saving your changes, OS X politely asks if you want to save this Smart Folder and warns that if you don’t save, the changes you made will be lost. You may be asked whether you want to replace the previous Smart Folder of the same name; usually, you do.

Smart Folders (with the exception of the Sidebar’s All My Files, which has its own weird little icon) display a little gear in their center, as shown in Figure 6-19, making them easy to tell apart from regular folders.

Smart Folders can save you a lot of time and effort, so if you haven’t played with them much (or at all) yet, be sure to give ’em a try.

6.5 Shuffling Around Files and Folders

Sometimes, keeping files and folders organized means moving them from one place to another. At other times, you want to copy them, rename them, or compress them to send to a friend. These sections explain all those things and more.All the techniques that I discuss in the following sections work at least as well for windows that use List, Column, or Cover Flow view as they do for windows that use Icon view. I use Icon view in the figures in this section only because it’s the best view for pictures to show you what’s going on. For what it’s worth, I find moving and copying files much easier in windows that use List or Column view.

6.5.1 Comprehending the Clipboard

Before you start moving your files around, let me introduce you to the Clipboard. The Clipboard is a holding area for the last thing that you cut or copied. That copied item can be text, a picture, a portion of a picture, an object in a drawing program, a column of numbers in a spreadsheet, any icon (except a disk), or just about anything else that can be selected. In other words, the Clipboard is the Mac’s temporary storage area.Most of the time, the Clipboard works quietly in the background, but you can ask the Clipboard to reveal itself by choosing Edit➪Show Clipboard. This command summons the Clipboard window, which lists the type of item (such as text, picture, or sound) on the Clipboard — and a message letting you know whether the item on the Clipboard can be displayed.

As a storage area, the Clipboard’s contents are temporary. Very temporary. When you cut or copy an item, that item remains on the Clipboard only until you cut or copy something else, logout, or restart. When you do cut or copy something else, the new item replaces the Clipboard’s contents, and the newcomer remains on the Clipboard until you cut or copy something else. And so it goes.

Whatever is on the Clipboard heads straight for oblivion if you crash, lose power, log out, or shut down your Mac, so don’t count on it too heavily or for too long.

The Clipboard commands on the Edit menu are enabled only when they can actually be used. If the selected item can be cut or copied, the Cut and Copy commands in the Edit menu are enabled. If the selected item can’t be cut or copied, the commands are unavailable and are dimmed (gray). If the Clipboard is empty or the current document can’t accept what’s on the Clipboard, the Paste command is dimmed. Finally, when nothing is selected, the Cut, Copy, and Clear commands are dimmed.

Icons can’t be cut; they can only be copied or pasted. So when an icon is selected, the Cut command is always gray.

6.5.2 Copying files and folders

One way to copy icons from one place to another is to use the Clipboard. When a file or folder icon is selected, choose Edit➪Copy (or use its shortcut, ⌘+C) to copy the selected icon to the Clipboard. Note that this doesn’t delete the selected item; it just makes a copy of it on the Clipboard. To paste the copied icon in another location, choose Edit➪Paste (or use its shortcut, ⌘+V).Other methods of copying icons from one place to another include these:

✓ Drag an icon from one folder icon onto another folder icon while holding down the Option key. Release the mouse button when the second folder is highlighted. This technique works regardless of whether the second folder’s window is open. If you don’t hold down the Option key, you move the icon to a new location rather than copy it, as I explain a little later in this section.You can cut an icon’s name, but you can’t cut the icon itself; you may only copy an icon. To achieve the effect of cutting an icon, select the icon, copy it to the Clipboard, paste it in its new location, and then move the original icon to the Trash.

When you copy something by dragging and dropping it with the Option key held down, the cursor changes to include a little plus sign (+) next to the arrow, as shown in the margin. Neat!

✓ Drag an icon into an open window for another folder while holding down the Option key. Drag the icon for the file or folder that you want to copy into the open window for a second folder (or other hard disk or removable media such as a USB flash drive).

✓ Choose File➪Duplicate (⌘+D) or right-click or Control-click the file or folder that you want to duplicate; then choose Duplicate from the contextual menu that appears. This makes a copy of the selected icon, adds the word copy to its name, and then places the copy in the same window as the original icon. You can use the Duplicate command on any icon except a disk icon.

You can’t duplicate an entire disk onto itself. But you can copy an entire disk (call it Disk 1) to any other actual, physical, separate disk (call it Disk 2) as long as Disk 2 has enough space available. Just hold down Option and drag Disk 1 onto Disk 2’s icon. The contents of Disk 1 are copied to Disk 2 and appear on Disk 2 in a folder named Disk 1.

If you’re wondering why anyone would ever want to copy a file, trust me: Someday, you will. Suppose that you have a file called Long Letter to Mom in a folder called Old Correspondence. You figure that Mom has forgotten that letter by now, and you want to send it again. But before you do, you want to change the date and delete the reference to Clarence, her pit bull, who passed away last year. So now you need to put a copy of Long Letter to Mom in your Current Correspondence folder. This technique yields the same result as making a copy of a file by using Save As, which I describe earlier in this chapter.

When you copy a file, it’s wise to change the name of the copied file. Having more than one file on your hard drive with exactly the same name isn’t a good idea, even if the files are in different folders. Trust me that having 12 files called Expense Report or 15 files named Doctor Mac Consulting Invoice can be confusing, no matter how well organized your folder structure is. Add distinguishing words or dates to file and folder names so that they’re named something more explicit, such as Expense Report Q3 2010 or Doctor Mac Consulting Invoice 4-4-2011.

You can have lots of files with the same name on the same disk (although, as I mention earlier, it’s probably not a good idea). But your Mac won’t let you have more than one file with the same name and extension (.txt, .jpg, .doc) in the same folder.

6.5.3 Pasting from the Clipboard

As I mention earlier in this chapter, to place the icon that’s on the Clipboard someplace new, click where you want the item to go, and choose Edit➪Paste or use the keyboard shortcut ⌘+V to paste what you’ve copied or cut.Pasting doesn’t purge the contents of the Clipboard. In fact, an item stays on the Clipboard until you cut, copy, restart, shut down, log out, or crash. This means that you can paste the same item over and over and over again, which can come in pretty handy at times.

Almost all programs have an Edit menu and use the Macintosh Clipboard, which means you can usually cut or copy something from a document in one program and paste it into a document in another program. Usually.

6.5.4 Moving files and folders

You can move files and folders around within a window to your heart’s content, as long as that window is set to Icon view. Just click and drag any icon to its new location in the window. Some people spend hours arranging icons in a window until they’re just so. But because using Icon view wastes so much screen space, I avoid using icons in a window.You can’t move icons around in a window that is displayed in List, Column, or Cover Flow view, which makes total sense when you think about it. (Well, you can move them to put them in a different folder in List, Column, or Cover Flow view, but that’s not moving them around, really.) And you can’t move icons around in a window under the spell of the Arrange By command.

As you probably expect from Apple by now, you have choices for how you move one file or folder into another folder. You can use these techniques to move any icon (folder, document, alias, or program icon) into folders or onto other disks.

If you want to move an item from one disk to another disk, you can’t use the preceding tricks. Your item is copied, not moved. If you want to move a file or folder from one disk to another, you have to hold down the ⌘ key when you drag an icon from one disk to another. The little Copying Files window even changes to read Moving Files. Nice touch, eh?✓ Drag an icon onto a folder icon. Drag the icon for one folder (or file) onto the icon for another folder (or disk) and then release when the second icon is highlighted (see Figure 6-20). The first folder is inside the second folder. Put another way, the first folder is a subfolder of the second folder. This technique works regardless of whether the second folder’s window is open.

✓ Drag an icon into an open folder’s window. Drag the icon for one folder (or file) into the open window for a second folder (or disk), as shown in Figure 6-20.

6.5.5 Selecting multiple icons

Sometimes you want to move or copy several items into a single folder. The process is pretty much the same as it is when you copy one file or folder (that is, you just drag the icon to where you want it and drop it there). But you need to select all the items you want before you can drag them en masse to their destination.If you want to move all the files in a particular folder, simply choose Edit➪Select All or press ⌘+A. This command selects all icons in the active window, regardless of whether you can see them onscreen. If no window is active, choosing Select All selects every icon on the Desktop.

But what if you want to select only some of the files in the active window or on the Desktop? Here’s the most convenient method:

1. To select more than one icon in a folder, do one of the following:

2. After you select the icons, click one of them (clicking anywhere else deselects the icons) and drag them to the location where you want to move them (or Option-drag to copy them).To deselect an icon, click it while holding down the ⌘ key.

- Click once within the folder window (don’t click any one icon), and drag your mouse (or keypad) while continuing to hold down the mouse button. You see an outline of a box around the icons while you drag, and all icons within or touching the box become highlighted (see Figure 6-21).

- Click one icon and hold down the Shift key while you click others. As long as you hold down the Shift key, each new icon that you click is added to the selection. To deselect an icon, click it a second time while still holding down the Shift key.

- Click one icon and hold down the ⌘ key while you click others. The difference between using the Shift and ⌘ keys is that the ⌘ key doesn’t select everything between it and the first item selected when your window is in List, Cover Flow, or Column view. In Icon view, it really doesn’t make much difference.

Be careful with multiple selections, especially when you drag icons to the Trash. You can easily — and accidentally — select more than one icon, so watch out that you don’t accidentally put the wrong icon in the Trash by not paying close attention. (I detail how the Trash icon works later in this chapter.)

6.5.6 Playing the icon name game: Renaming icons

Icon, icon, bo-bicon, banana-fanna fo-ficon. Betcha can change the name of any old icon! Well, that’s not entirely true. . . .If an icon is locked or busy (the application is currently open), or if you don’t have the owner’s permission to rename that icon (see Chapter 16 for details about permissions), you can’t rename it. Similarly, you should never rename certain reserved icons (such as the Library, System, and Desktop folders).

To rename an icon, you can either click the icon’s name directly (don’t click the icon itself because that selects the icon) or click the icon and press Return (or Enter) once.

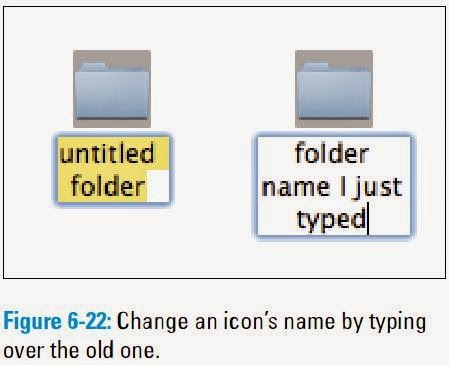

Either way, the icon’s name is selected and surrounded with a box, and you can type a new name, as shown in Figure 6-22. In addition, the cursor changes from a pointer to a text-editing I-beam. An I-beam cursor is the Mac’s way of telling you that you can type now. At this point, if you click the I-beam cursor anywhere in the name box, you can edit the icon’s original name. If you don’t click the I-beam cursor in the name box but just begin typing, the icon’s original name is replaced by what you type.

Either way, the icon’s name is selected and surrounded with a box, and you can type a new name, as shown in Figure 6-22. In addition, the cursor changes from a pointer to a text-editing I-beam. An I-beam cursor is the Mac’s way of telling you that you can type now. At this point, if you click the I-beam cursor anywhere in the name box, you can edit the icon’s original name. If you don’t click the I-beam cursor in the name box but just begin typing, the icon’s original name is replaced by what you type.If you’ve never changed an icon’s name, give it a try. And don’t forget: If you click the icon itself, the icon is selected, and you won’t be able to change its name. If you do accidentally select the icon, just press Return (or Enter) once to edit the name of the icon.

One last thing: If you have two or more icons you want to move to a new folder, select the items and choose File➪New Folder with Selection, press ⌘+Control+N, or right-click or Control-click one of the selected items and choose New Folder with Selection. All three techniques will create a new folder, move the selected icons into it, and select the name of the new folder (which will be New Folder with Items) so you can type its new name immediately.

6.5.7 Compressing files

If you’re going to send files as an e-mail enclosure, creating a compressed archive of the files first and sending the archive instead of the originals usually saves you time sending the files and saves the recipient time downloading them. To create this compressed archive, simply select the file or files and then choose File➪Compress. This creates a compressed .zip file out of your selection. The compressed file is smaller than the original — sometimes by quite a bit.6.5.8 Getting rid of icons

To get rid of an icon — any icon — merely drag it onto the Trash icon in your Dock.Trashing an alias gets rid of only the alias, not the parent file. But trashing a document, folder, or application icon puts it in the Trash, where it will be deleted permanently the next time you empty the Trash. The Finder menu offers a couple of commands that help you manage the Trash:

✓ Finder➪Empty Trash: This command deletes all items in the Trash from your hard drive, period.If you put something in the Trash by accident, you can almost always return it from whence it came: Just invoke the magical Undo command. Choose Edit➪Undo or press ⌘+Z. The accidentally trashed file returns to its original location. Usually. Unfortunately, Undo doesn’t work every time — and it remembers only the very last action that you performed when it does work — so don’t rely on it too much.

I’ll probably say this more than once: Use this command with a modicum of caution. After a file is dragged into the Trash and the Trash is emptied, the file is gone, gone, gone unless you have a Time Machine or other backup. (Okay, maybe ProSoft Engineering’s Data Rescue II or some other third-party utility can bring it back, but I wouldn’t bet the farm on it.)

✓ Finder➪Secure Empty Trash: Choosing this command makes the chance of recovery by even the most ardent hacker or expensive diskrecovery tool difficult to virtually impossible. Now the portion of the disk that held the files you’re deleting will be overwritten with randomly generated gibberish. You’re hosed unless you have a Time Machine or other backup.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий