Windows are a ubiquitous part of using a Mac. When you open a folder, you see a window. When you write a letter, the document that you’re working on appears in a window. When you browse the Internet, web pages appear in a window . . . and so on.

For the most part, windows are windows from program to program. You’ll probably notice that some programs (Adobe Photoshop or Microsoft Word, for example) take liberties with windows by adding features (such as pop-up menus), custom toolbars, or textual information (such as zoom percentage or file size) that may appear around the edges of the document window.

Don’t let it bug you; that extra fluff is just window dressing (pun intended). Maintaining the window metaphor, many information windows display different kinds of information in different panes, or discrete sections within the window.

When you finish this chapter, which focuses exclusively on OS X Finder windows, you’ll know how to use most windows in most applications.

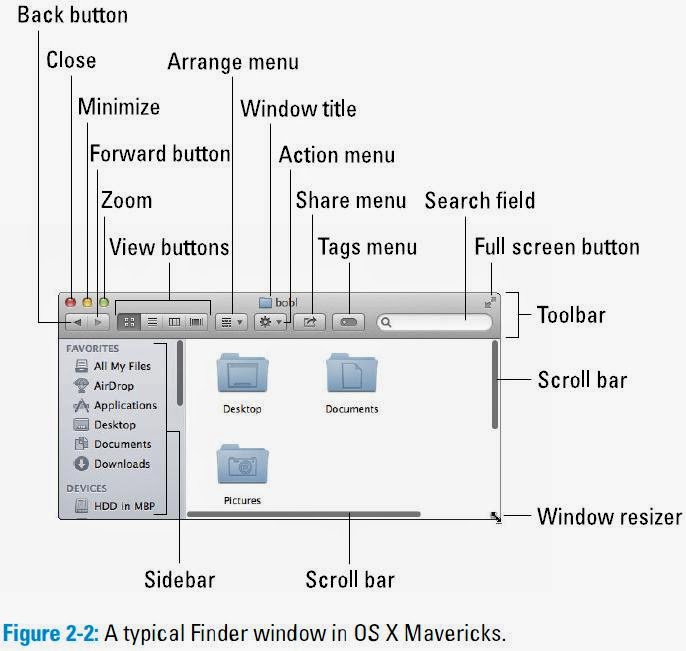

And so, without further ado, the following list gives you a look at the main features of a typical Finder window (as shown in Figure 2-2). I discuss these features in greater detail in later sections of this chapter.

If your windows don’t look exactly like the one shown in Figure 2-2, don’t be concerned. You can make your windows look and feel any way you like. As I explain later in the “Working with Windows” section, moving and resizing windows are easy tasks. Chapter 3 explains how to customize certain window features. Chapter 5 focuses on ways you can change a window’s view, specifically when you’re using the Finder.

Meanwhile, here’s what you see (clockwise from top left):

✓ Close, Minimize, and Zoom (gumdrop) buttons: Shut ’em, shrink and place ’em in the Dock, and make ’em grow.

✓ View buttons: Choose among four exciting views of your window: Icon, List, Column, and Cover Flow. Find out more about views in Chapter 5.

✓ Arrange menu: Click this little doohickey to arrange this window’s icons by Kind, Application, Date Modified, Date Created, Date Last Opened, Date Added, Size, or Label. Or, of course, by None.

✓ Action menu: This button is really a pop-up menu of commands you can apply to currently selected items in the Finder window or on the Desktop. (These are generally the same commands you’d see in the shortcut menu if you right-clicked or Control-clicked the same items.)

✓ Window title: Shows the name of the window. ⌘-click the name of the window to see a pop-up menu with the complete path to this folder (try it). This tip applies to most windows you’ll encounter, not just Finder windows. So ⌘-click a window’s title, and you’ll usually see the path to its enclosing folder on your disk.

You can also have the path displayed at the bottom of every Finder window by choosing View➪Show Path Bar, as shown in the active window (Applications) if you look ahead to Figure 2-4.

✓ Share menu: Another button that’s actually a menu; click it to share selected files or folders via e-mail, Messages, or AirDrop.

✓ Tags menu: Yet another button/menu; click it to assign a tag to the selected files or folders.

✓ Search field: Type a string of characters here, and OS X Mavericks digs into your system to find items that match by filename or document contents (yes, words within documents).

✓ Full screen button: Click it to expand the window to full screen.

✓ Toolbar: Buttons for frequently used commands and actions.

✓ Scroll bars: Use the scroll bars for moving around a window.

✓ Sidebar: Frequently used items live here.

✓ Window Resizer: This helpful little visual cue appears when you hover over an edge or corner of a window, or over the dividing line between two panes in the same window (the sidebar and main area of Finder windows, for example). If you click a Resizer, you can then drag the edge, corner, or dividing line to resize the window or pane.

✓ Forward and Back buttons: These buttons take you to the next or previous folder displayed in this particular window.

If you’re familiar with web browsers, the Forward and Back buttons in the Finder work the same way. The first time you open a window, neither button is active. But as you navigate from folder to folder, these buttons remember your breadcrumb trail so you can quickly traverse backward or forward, window by window. You can even navigate this way from the keyboard by using the shortcuts ⌘+[ for Back and ⌘+] for Forward.

The Forward and Back buttons remember only the other folders you’ve visited that appear in that open window. If you’ve set a Finder Preference so that a folder always opens in a new window — or if you forced a folder to open in a new window, which I describe in a bit — the Forward and Back buttons won’t work. You have to use the modern, OS X–style window option, which uses a single window, or the buttons are useless.

Kudos to Apple for fixing something I ranted about in earlier editions of this book. In Snow Leopard and earlier releases of OS X, if you hid the toolbar, the Sidebar was also hidden, whether you liked it or not. Conversely, if you wanted to see the toolbar, you’d have to see the Sidebar as well. Mavericks gives you the flexibility to show or hide them independently in its View menu, as you see in Chapter 5.

✓ Close (red): Click this button to close the window.

✓ Minimize (yellow): Click this button to minimize the window. Clicking Minimize appears to close the window, but instead of making it disappear, Minimize adds an icon for the window to the right side of the Dock.

See the section about minimizing windows into application icons in Chapter 4 if a document icon doesn’t appear in your Dock when you minimize its window.

To view the window again, click the Dock icon for the window that you minimized. If the window happens to be a QuickTime movie, the movie continues to play, albeit at postage-stamp size, in its icon in the Dock. (I discuss the Dock in detail in Chapter 4.)

✓ Zoom (green): Click this button to make the window larger or smaller, depending on its current size. If you’re looking at a standard-size window, clicking Zoom usually makes it bigger. (I say usually because if the window is larger than its contents, clicking this button shrinks the window to the smallest size that can completely enclose the contents without scrolling.) Click the Zoom button again to return the window to its previous size.

Simply click and drag a scroll bar to move it up or down or side to side.

If your scroll bars don’t look exactly like the ones in Figure 2-3 or work as described in the following list, don’t worry. These are System Preferences you can configure to your heart’s desire, but you’ll have to wait until Chapter 3 to find out how.

Here are some ways you can scroll in a window:

✓ Click a scroll bar and drag. The content of the window scrolls proportionally to how far you drag the scroll bar.

✓ Click in the scroll bar area but don’t click the scroll bar itself. The window scrolls either one page up (if you click above the scroll bar) or down (if you click below the scroll bar). You can change a setting in your General System Preference pane to cause the window to scroll proportionally to where you click.

For what it’s worth, the Page Up and Page Down keys on your keyboard function the same way as clicking the grayish scroll bar area (the vertical scroll bar only) in the Finder and many applications. But these keys don’t work in every program; don’t become too dependent on them. Also, if you’ve purchased a mouse, trackball, or other pointing device that has a scroll wheel, you can scroll vertically in the active (front) window with the scroll wheel or press and hold the Shift key to scroll horizontally. Alas, this horizontal scrolling-with-the-Shift-key works in Finder windows, but not in all applications. For example, it works in Apple’s TextEdit application, but not in Microsoft Word.

✓ Use the keyboard. In the Finder, first click an icon in the window and then use the arrow keys to move up, down, left, or right. Using an arrow key selects the next icon in the direction it indicates — and automatically scrolls the window, if necessary. In other programs, you might or might not be able to use the keyboard to scroll. The best advice I can give you is to try it — either it’ll work or it won’t.

✓ Use a two-finger swipe (on a trackpad). If you have a notebook with a trackpad or use a Magic Trackpad or Magic Mouse, just move the arrow cursor over the window and then swipe the trackpad with two fingers to scroll.

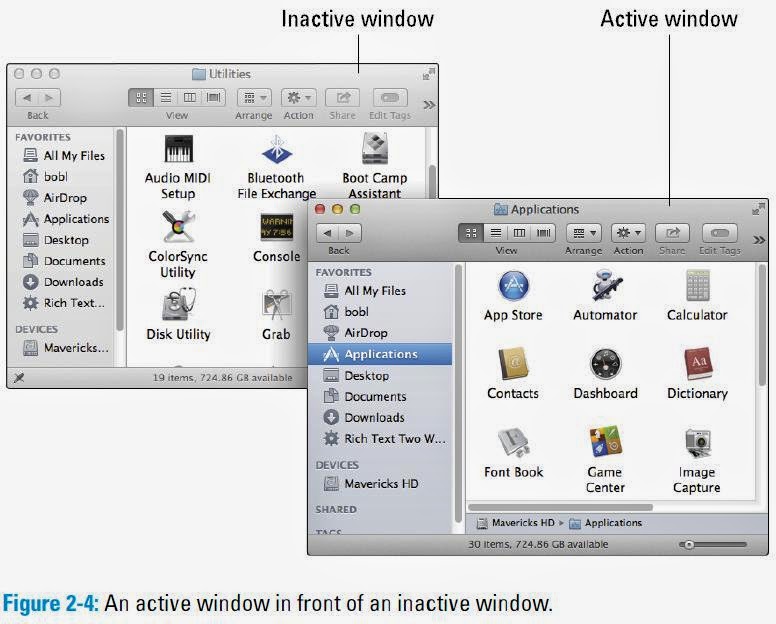

Look at Figure 2-4 for an example of an active window in front of an inactive window (the Applications window and the Utilities window, respectively).

The following is a list of the major visual cues that distinguish active from inactive windows:

✓ The active window’s title bar: The Close, Minimize, and Zoom buttons are red, yellow, and green. The inactive windows’ buttons are not. This is a nice visual cue — colored items are active, and gray ones are inactive. Better still, if you move your mouse over an inactive window’s gumdrop buttons, they light up in their usual colors so you can close, minimize, or zoom an inactive window without first making it active. Neat!

✓ Other buttons and scroll bars in an active window: They’re bright. In an inactive window, these features are grayed out and more subdued.

✓ Bigger and darker drop shadows in an active window: They grab your attention more than those of inactive windows and trick your eye into thinking the active window is further away from the background than the inactive one.

For the most part, windows are windows from program to program. You’ll probably notice that some programs (Adobe Photoshop or Microsoft Word, for example) take liberties with windows by adding features (such as pop-up menus), custom toolbars, or textual information (such as zoom percentage or file size) that may appear around the edges of the document window.

Don’t let it bug you; that extra fluff is just window dressing (pun intended). Maintaining the window metaphor, many information windows display different kinds of information in different panes, or discrete sections within the window.

When you finish this chapter, which focuses exclusively on OS X Finder windows, you’ll know how to use most windows in most applications.

And so, without further ado, the following list gives you a look at the main features of a typical Finder window (as shown in Figure 2-2). I discuss these features in greater detail in later sections of this chapter.

If your windows don’t look exactly like the one shown in Figure 2-2, don’t be concerned. You can make your windows look and feel any way you like. As I explain later in the “Working with Windows” section, moving and resizing windows are easy tasks. Chapter 3 explains how to customize certain window features. Chapter 5 focuses on ways you can change a window’s view, specifically when you’re using the Finder.

Meanwhile, here’s what you see (clockwise from top left):

✓ Close, Minimize, and Zoom (gumdrop) buttons: Shut ’em, shrink and place ’em in the Dock, and make ’em grow.

✓ View buttons: Choose among four exciting views of your window: Icon, List, Column, and Cover Flow. Find out more about views in Chapter 5.

✓ Arrange menu: Click this little doohickey to arrange this window’s icons by Kind, Application, Date Modified, Date Created, Date Last Opened, Date Added, Size, or Label. Or, of course, by None.

✓ Action menu: This button is really a pop-up menu of commands you can apply to currently selected items in the Finder window or on the Desktop. (These are generally the same commands you’d see in the shortcut menu if you right-clicked or Control-clicked the same items.)

✓ Window title: Shows the name of the window. ⌘-click the name of the window to see a pop-up menu with the complete path to this folder (try it). This tip applies to most windows you’ll encounter, not just Finder windows. So ⌘-click a window’s title, and you’ll usually see the path to its enclosing folder on your disk.

You can also have the path displayed at the bottom of every Finder window by choosing View➪Show Path Bar, as shown in the active window (Applications) if you look ahead to Figure 2-4.

✓ Share menu: Another button that’s actually a menu; click it to share selected files or folders via e-mail, Messages, or AirDrop.

✓ Tags menu: Yet another button/menu; click it to assign a tag to the selected files or folders.

✓ Search field: Type a string of characters here, and OS X Mavericks digs into your system to find items that match by filename or document contents (yes, words within documents).

✓ Full screen button: Click it to expand the window to full screen.

✓ Toolbar: Buttons for frequently used commands and actions.

✓ Scroll bars: Use the scroll bars for moving around a window.

✓ Sidebar: Frequently used items live here.

✓ Window Resizer: This helpful little visual cue appears when you hover over an edge or corner of a window, or over the dividing line between two panes in the same window (the sidebar and main area of Finder windows, for example). If you click a Resizer, you can then drag the edge, corner, or dividing line to resize the window or pane.

✓ Forward and Back buttons: These buttons take you to the next or previous folder displayed in this particular window.

If you’re familiar with web browsers, the Forward and Back buttons in the Finder work the same way. The first time you open a window, neither button is active. But as you navigate from folder to folder, these buttons remember your breadcrumb trail so you can quickly traverse backward or forward, window by window. You can even navigate this way from the keyboard by using the shortcuts ⌘+[ for Back and ⌘+] for Forward.

The Forward and Back buttons remember only the other folders you’ve visited that appear in that open window. If you’ve set a Finder Preference so that a folder always opens in a new window — or if you forced a folder to open in a new window, which I describe in a bit — the Forward and Back buttons won’t work. You have to use the modern, OS X–style window option, which uses a single window, or the buttons are useless.

Kudos to Apple for fixing something I ranted about in earlier editions of this book. In Snow Leopard and earlier releases of OS X, if you hid the toolbar, the Sidebar was also hidden, whether you liked it or not. Conversely, if you wanted to see the toolbar, you’d have to see the Sidebar as well. Mavericks gives you the flexibility to show or hide them independently in its View menu, as you see in Chapter 5.

Top o’ the window to ya!

Take a gander at the top of a window — any window. You see three buttons in the top-left corner and the name of the window in the top center. The three buttons (called gumdrop buttons by some folks because they look like, well, gumdrops) are officially known as Close, Minimize, and Zoom, and their colors (red, yellow, and green, respectively) pop off the screen. Here’s what they do:✓ Close (red): Click this button to close the window.

✓ Minimize (yellow): Click this button to minimize the window. Clicking Minimize appears to close the window, but instead of making it disappear, Minimize adds an icon for the window to the right side of the Dock.

See the section about minimizing windows into application icons in Chapter 4 if a document icon doesn’t appear in your Dock when you minimize its window.

To view the window again, click the Dock icon for the window that you minimized. If the window happens to be a QuickTime movie, the movie continues to play, albeit at postage-stamp size, in its icon in the Dock. (I discuss the Dock in detail in Chapter 4.)

✓ Zoom (green): Click this button to make the window larger or smaller, depending on its current size. If you’re looking at a standard-size window, clicking Zoom usually makes it bigger. (I say usually because if the window is larger than its contents, clicking this button shrinks the window to the smallest size that can completely enclose the contents without scrolling.) Click the Zoom button again to return the window to its previous size.

A scroll new world

Yet another way to see more of what’s in a window or pane is to scroll through it. Scroll bars appear at the bottom and right sides of any window or pane that contains more stuff — icons, text, pixels, or whatever — than you can see in the window. Figure 2-3, for example, shows two instances of the same window: Dragging the scroll bar on the right side of the front window reveals the items above Dashboard and Dictionary and below Game Center and Image Capture (that is, items that are visible in the expanded window in the background). Dragging the scroll bar on the bottom of the window reveals items to the left and right, such as Font Book, Mail, Launchpad, and Notes.Simply click and drag a scroll bar to move it up or down or side to side.

If your scroll bars don’t look exactly like the ones in Figure 2-3 or work as described in the following list, don’t worry. These are System Preferences you can configure to your heart’s desire, but you’ll have to wait until Chapter 3 to find out how.

Here are some ways you can scroll in a window:

✓ Click a scroll bar and drag. The content of the window scrolls proportionally to how far you drag the scroll bar.

✓ Click in the scroll bar area but don’t click the scroll bar itself. The window scrolls either one page up (if you click above the scroll bar) or down (if you click below the scroll bar). You can change a setting in your General System Preference pane to cause the window to scroll proportionally to where you click.

For what it’s worth, the Page Up and Page Down keys on your keyboard function the same way as clicking the grayish scroll bar area (the vertical scroll bar only) in the Finder and many applications. But these keys don’t work in every program; don’t become too dependent on them. Also, if you’ve purchased a mouse, trackball, or other pointing device that has a scroll wheel, you can scroll vertically in the active (front) window with the scroll wheel or press and hold the Shift key to scroll horizontally. Alas, this horizontal scrolling-with-the-Shift-key works in Finder windows, but not in all applications. For example, it works in Apple’s TextEdit application, but not in Microsoft Word.

✓ Use the keyboard. In the Finder, first click an icon in the window and then use the arrow keys to move up, down, left, or right. Using an arrow key selects the next icon in the direction it indicates — and automatically scrolls the window, if necessary. In other programs, you might or might not be able to use the keyboard to scroll. The best advice I can give you is to try it — either it’ll work or it won’t.

✓ Use a two-finger swipe (on a trackpad). If you have a notebook with a trackpad or use a Magic Trackpad or Magic Mouse, just move the arrow cursor over the window and then swipe the trackpad with two fingers to scroll.

(Hyper)Active windows

To work within a window, the window must be active. The active window is always the frontmost window, and inactive windows always appear behind the active window. Only one window can be active at a time. To make a window active, click it anywhere — in the middle, on the title bar, or on a scroll bar. It doesn’t matter where; just click anywhere to activate it.Look at Figure 2-4 for an example of an active window in front of an inactive window (the Applications window and the Utilities window, respectively).

The following is a list of the major visual cues that distinguish active from inactive windows:

✓ The active window’s title bar: The Close, Minimize, and Zoom buttons are red, yellow, and green. The inactive windows’ buttons are not. This is a nice visual cue — colored items are active, and gray ones are inactive. Better still, if you move your mouse over an inactive window’s gumdrop buttons, they light up in their usual colors so you can close, minimize, or zoom an inactive window without first making it active. Neat!

✓ Other buttons and scroll bars in an active window: They’re bright. In an inactive window, these features are grayed out and more subdued.

✓ Bigger and darker drop shadows in an active window: They grab your attention more than those of inactive windows and trick your eye into thinking the active window is further away from the background than the inactive one.

Комментариев нет:

Отправить комментарий